In the days before Facebook, police reporters visited families that suffered sudden, tragic loss to request a photo of their loved one to print in the local newspaper. You’d think families resented the intrusion, but the opposite was more often the case. Grieving parents typically invited the reporter into their home, as if press interest validated the fact their child’s death mattered, that even strangers cared.

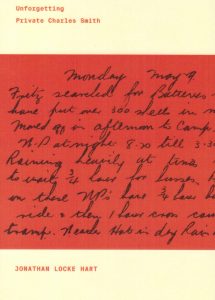

This same sentiment must have prompted Mr. and Mrs. Smith of 16 Geneva Avenue to deposit their lost son Charlie’s diary with the Baldwin Collection of Canadiana at the Toronto Reference Library. He was a good boy who died tragically. He mattered. And there his diary sat in a box, year after year, until it was discovered by poet Jonathan Locke Hart and transformed into this beautiful book, Unforgetting Private Charles Smith.

“Smith was not writing to express himself, to record his thoughts, his emotions, his opinions,” writes the author. “He was simply writing down what happened, in telegraphic style.”

Smith, 22, was on leave as an accountant with Webb, Read, Hogan & Callingham Co. Ltd. of Toronto when he was killed at the Battle of Mount Sorrel in Belgium in 1916. In a single surviving photograph, he appears as a skinny youth trying to grow a moustache. Charlie’s penmanship was excellent. Like many 22-year olds he liked girls, and especially food:

- Pay day: we had a grand feed. Roast beef

- Potatoes, salad, rum cake, apples, café.

And on his last New Year’s, with only months to live:

- We had a great New Year’s feed. Jenny fixed up

- Two chickens with rice, pickles, rolls, tomato sauce,

- Plum pudding, cake, apples, cigs, coffee.

- A full feeling afterwards. Weather fine:

- It rained for about two hours.

Author Locke Hart documents Private Smith’s diary in poetic style, stark and sad and funny, from his departure for the Western Front to the last entry on May 31, 1916: “Back at 11 am.” Smith confided he met a girl in Dieppe, marveled at aerial dogfights over the trenches, called the Germans “Fritz”, described the moaning of artillery shells and chirping of skylarks on night patrol, and the tedium of standing at attention for VIP visits:

- The Minister of Militia

- And High Commissioner kept us standing

- About for two hours. Tradesmen soak us.

In April 1916 Smith took his last leave to London where the girls were “bold”, he wrote.

- I had a bath, bed, pajamas, dressing gown

- And slippers. I hardly recognized

- Myself. The weather was good.

Weeks later Charlie cursed his luck. He was struck by shrapnel but it was “only a bruise”: “I suffered a little from shock; I felt nervous. I am sorry it was not a blighty one” – a wound just serious enough to send a soldier back to Old Blighty, the U.K., and a clean bed in a hospital ward.

In a month he was dead. No photo appeared in the local paper. Smith’s death was dismissed with a single, short paragraph in that day’s Toronto casualty list along with McAllister the mailman, and Probin the realtor, Travers the bank clerk and Private Jones of Ferndale Avenue, who used to teach Baptist Sunday School.

Unforgetting Private Charles Smith is haunting, like the smiling photo of a crime victim in the pages of a newspaper. His death mattered.

By Holly Doan

Unforgetting Private Charles Smith, by Jonathan Locke Hart; Athabasca University Press; 80 pages; ISBN 9781-77199-2534; $19.99