Dr. Peter Edmund Jones is the most interesting Canadian you never heard of. His accomplishments were many, yet he died in poverty. He left a mark in science and public affairs, yet stumbled in drunkenness and despair.

The son of a Mississauga chief and English mother, Jones was the first Status Indian to graduate from a Canadian medical school, Queen’s University in 1866. His thesis was “The Indian Medicine Man.” Jones was the first to publish an Indigenous newspaper in Canada, The Indian, in 1886. He was a chess master, an archaeological advisor to the Smithsonian Institute, a political organizer for John A. Macdonald, a federal Indian agent.

“Jones appears to have been a romantic who felt his early success would carry him onwards,” writes biographer Allan Sherwin. Of course this could only end badly. To read Bridging Two Peoples is to sense the creep of petty humiliation and raw bigotry that crushed this Victorian romantic in the end.

When Jones married a widow with three sons in 1873 he could not legally adopt his own stepchildren since Status Indians were unable to file applications in court. When Jones was appointed an Indian agent in 1888 he was paid 40 percent less than white agents. When he retired in 1903 Jones was reduced to suing the Grand Trunk Railway for $10 after a boorish conductor threw his wife off a train for refusing to sit in a second-class car.

Biographer Sherwin, a professor emeritus of neurology at McGill University, crisply recounts the life of this extraordinary man. “He believed that effort and education would enable Aboriginals to compete with their Euro-Canadian neighbours, and he tried to act as a bridge between them,” writes Sherwin. “Dr. Jones had made the mistake of trying to act as leader of his people from outside the reserve.”

Of the many indignities was an 1875 item in the Toronto Mail that characterized Indians as a low, lazy, treacherous race. “I am one of the Mississaugas,” wrote Jones, the band chief and a practicing physicia. “There is not in Canada a tribe of Indians more clean, industrious, and sharp in business, than are my people…Our women are treated as much like ladies as the wives of the white farmers about here.”

Jones died penniless in Hagersville, Ont., his savings lost to failed ventures and the alcoholism that cost his dismissal as an Indian agent in 1897. “The sale of alcohol to Indigenous peoples was a crime under federal law, but an exception might be made in the case of a valid prescription,” recounts Sherwin. “According to Indian Affairs’ records, Dr. Jones did purchase alcohol on behalf of his patients and, like many doctors of that era, was subjected to temptation.”

Jones, in the end, self-destructed. In Victorian Canada he could have done no less.

By Holly Doan

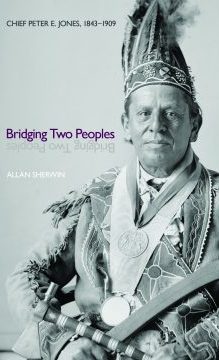

Bridging Two Peoples: Chief Peter E. Jones, 1843-1909 by Allan Sherwin; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 270 pages; ISBN 978-1-55458-633-2; $29.95