(Editor’s note: Professor Stephen Endicott of York University died in 2019 at 91. He spent years attempting to rehabilitate his late father, Reverend James Endicott, recipient of the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize for his work as a Canadian peace activist. Endicott, a former member of the Communist Party, on October 7, 2009 spoke to Blacklock’s publisher Holly Doan on his father and the Cold War era. Following is a transcription of his remarks)

It’s the only existing Stalin Peace Prize left in the world. My father proposed to give it to Library and Archives Canada when a suitable climate for receiving it would appear. It didn’t happen in his lifetime. It’s kept in a bank vault.

He died in 1993. He was 94. My father used to say, “I’ve lived so long, I have no more enemies.” He outlived them all.

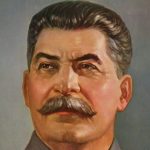

Why did he accept the Prize? He was glad to. He felt honoured. This Prize was sort of like the Nobel Peace Prize for the East Bloc. Stalin was a very respected figure at that time. There was no problem.

He knew it would create some controversy at home. He was Public Enemy Number One in those years. The cabinet even considered trying him for treason. The Winnipeg Tribune called him a Judas. Oh, I’m still angry about it. But then, that’s part of the struggle. Some people tried to set fire to our house.

My father thought it helped to go to the USSR. He said, “It’s easy to make peace with your friends. It’s harder to make peace with your enemies – and you should find out about them.”

The press always tried to dismiss the peace movement as a Communist front, that “Joe Stalin says we’ve got to ban the bomb and disarm.” My father snapped back, “Just because Joe Stalin says two plus two equals four, I’m not going to stop saying it.”

Canadians were told the Cold War was a fight between democracy and autocracy, and we were threatened somehow and therefore we should be ready. There was a tremendous amount of war propaganda from the United States.

I think people were misled into to thinking we were in imminent danger of some kind of attack. People I was associated with went around distributing leaflets and putting up stickers saying, “No Canadian troops for Yankee war in Korea!”

Later, the revelations about Stalin’s terror and so on, that was years away. Revelations about Stalin’s misdeeds were a terrible blow. It was a time for questions. That cast a shadow over the late 1950s, and it caused me to leave political organizing.

The United Church, my father’s church, years later apologized to him. Only twice in the history of the United Church has it apologized to anybody: Once to the native people in Canada, and the second time to James Endicott.