In the days before television, newsreel producers each year assigned cameras to film three visually rich, set-piece spectacles that represented Canada to theatre audiences nationwide: the opening of Parliament, the Calgary Stampede and the Eaton’s Santa Claus parade. One of these is gone.

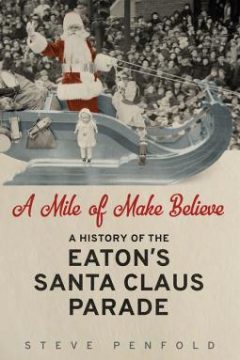

A Mile Of Make Believe recounts with warmth and nostalgia the Christmas extravaganza sponsored by a family-owned corporation once the largest retailer in the country. This is not a dry municipal history. Eaton’s in its heyday sponsored Santa parades from Edmonton to Montréal. Author Steve Penfold, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, has crafted a smart and funny account of a lost piece of Canadiana.

Nobody did more than Eaton’s to take the Christ out of Christmas. “The Santa Claus parade was a spectacle of capitalist non-realism,” writes Penfold. Organizers specifically excluded religious imagery. If the 1920 parade featured Noah’s Ark, the star of the float was a monkey smoking a pipe. Penfold recounts an incident at the 1968 event when an elderly protester shouted, “This is not a parade for God, this is a parade for the devil.” One mother replied: “For crying out loud, will you shut up.”

Eaton’s did not invent the Santa parade. A Mile Of Make-Believe traces the roots of the retail observance to a local department store sponsorship in Peoria, Illinois in 1888. Yet none eclipsed Eaton’s in scale or scope. It was “an assault on the eyes and ears,” writes Penfold. One Toronto parade featured a Mother Goose float that filled half a city block. The Montréal parade was fronted by the military band for the Black Watch pounding out Jingle Bells.

“The company expended stunning resources on the events,” says Penfold. “By the 1950s, the parade ate up more than half the company’s public relations budget,” the equivalent of $1.3 million at its peak.

“As a corporate spectacle that experienced its golden years in the middle decades of the twentieth century, the Eaton’s Santa Claus was one example of a powerful new form of commercial life and culture holiday – the Christmas pageant,” the author notes.

The producer of the longest-running Toronto spectacle was Jack Brockie. He joined Eaton’s in 1914 and for decades ran a year-round team of carpenters and seamstresses preparing for the Christmas wonder. Brockie was the “man in the grey flannel suit with an eye for colour” and a love of children. “Every year I go along University Avenue and look at the expressions on their faces – white faces, black faces, yellow faces, along together for their Santa,” Brockie wrote a friend.

A Mile Of Make-Believe is also an affectionate tribute to a corporate giant. In 1969 the company had 48 stores and a payroll of 50,000 employees, the fourth-largest employer in Canada. Eaton’s ran purchasing offices in London, Paris, New York, Yokohama and Kobe. As late as 1975 it remained the largest retailer in Canada, eclipsed only by Hudson’s Bay the following year.

It ended pathetically. Eaton’s dropped its parade sponsorship as an austerity measure in 1982 and collapsed in bankruptcy in 1999. We are left with memories and newsreel images of blaring bands and a fifty-foot alligator slithering down University Avenue.

By Holly Doan

A Mile of Make-Believe: A History of the Eaton’s Santa Claus Parade, by Steve Penfold; University of Toronto Press; 256 pages; ISBN 9781-4426-29240; $27.95