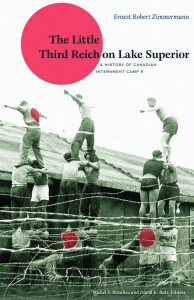

Hitler’s publicist once spent the winter in Red Rock, Ont., humming the Horst Wessel Song and cursing his fate. In the carnival of Canadian oddities, none is more curious than The Little Third Reich On Lake Superior. Historian Ernest Zimmerman of Lakehead University chronicles the strange events that saw 1,150 men and boys – Jews and Nazis alike – herded into bunkhouses northeast of Thunder Bay in the winter of 1940.

It was a “third-rate jungle prison,” one inmate recalled. Another complained it was like being kidnapped and dragged into the wilderness. “They deeply resented the treatment,” Zimmerman writes. “They resented being in foreign surroundings, away from home, and being treated as prisoners of war rather than refugees.”

Professor Zimmerman died in 2008, still working on his manuscript. His drafts and notes were compiled into this lively chronice by two Lakehead historians, Michel Beaulieu and David Ratz.

On May 30, 1940 Britain’s wartime cabinet asked Canada to take 35,000 enemy aliens off its hands. Note the date: German U-boats were prowling the Atlantic; Norway, France and the Low Countries had fallen to the Nazis; Britain feared imminent attack. “The rationale was that in the event of a German invasion, the threat of a ‘fifth column’ would be reduced,” Zimmerman writes.

Deportees were a mix of merchant sailors, Hitler youth, Jewish refugees and pretty much anyone with a German passport now branded a security risk. “Instead of using the deportation as an opportunity to distinguish real Nazis from actual non-Nazis, the selection process for deportation degenerated into a ‘mere juggling of numbers, as if a train timetable were being arranged, and not the disposition of human beings,’” notes Little Third Reich.

They were banished to Québec City aboard the Canadian Pacific liner Duchess Of York and put on a passenger train for the two-day journey to internment at an abandoned paper mill. Little Third Reich counts 26 such camps nationwide from Kananaskis Park in Alberta to Montréal’s St. Helen’s Island, future site of Expo 67. None were bigger than Camp R at Red Rock.

Refugees and Nazis “viewed each other with ‘horror and loathing’,” Zimmerman writes, yet camp life settled into a passable routine with few incidents save occasional fistfights and crude score-settling. When the camp commander ordered kitchen staff to prepare a kosher meal for Chanukah, Nazi cooks instead served bacon. “In general there is a fairly friendly atmosphere in the camp,” a visiting officer wrote. “However, there will always be tension while there are two intensely hostile groups.”

Inmates had radios and movie nights, swam in Lake Superior and organized boxing tournaments and a brass band. Food was plentiful – “never the same soup two days in a row” – and prisoners whiled away the hours at a woodshop making handicrafts to sell in the drugstore at nearby Nipigon, Ont. Ships in a bottle sold for $1.75. “There is just no variety at all,” lamented one inmate. “Every day, roll call, meals, another roll call, bed. You lose your sense of time.” There were worse ways to spend the war.

Camp R was home to minor celebrities. Inmates included a cousin of the Red Baron, a foreign correspondent for the liberal daily Vossische Zeitung, the first newspaper to serialize the anti-war novel All Quiet On The Western Front, and Ernst Hanfstaengl, a Bavarian bon vivant who’d served as publicity agent for Adolf Hitler in the early years and claimed to have invented the salute “Sieg Heil.”

The camp lasted sixteen months, a peculiar corner of the war in Northern Ontario. No plaque marks the site.

By Holly Doan

The Little Third Reich On Lake Superior by Ernest R. Zimmerman; University of Alberta Press; 384 pages; ISBN 9780-8886-46736; $29.95