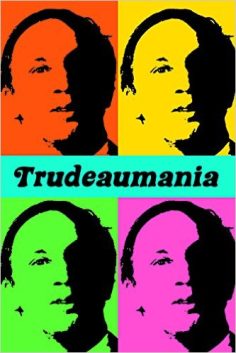

1968 is so layered in mythology it takes a surgeon’s scalpel to cut to the facts. Historian Paul Litt of Carleton University deftly slices and trims until the truth emerges in Trudeaumania. Even in death Pierre Trudeau remains a polarizing figure. Professor Litt traces the phenomenon to that long-ago campaign.

Yes, Trudeaumania was invented by media, writes Litt: “Yet the media could not have made Trudeau without a complicit audience.” Most strikingly, it could never happen exactly the same way again. The ’68 phenomenon was a collision at the intersection of time and place. Many political fixers have schemed to recreate the experience, and many have failed.

“For those caught up in the mania, 1968 was a historic turning point in which Canada left its dowdy colonial past behind and assumed a new autonomous identity as a model modern liberal democracy,” writes Litt. “They may have been deluding themselves, but since nations are fictions with real-world effects, Trudeaumania had lasting influence.”

Professor Litt is a tireless researcher and honest correspondent. He is the first to chronicle worries over Trudeau’s sexuality, serious enough to alarm Liberal organizers. Hard-bitten CBC newsman Norman DePoe once interviewed Trudeau at the Chateau Laurier pool, “known in Ottawa as a gay pickup spot,” recounts Litt. “Trudeau reclined in a lounge chair with his chin on the back of a hand supported by a folded wrist, a bit of body language coded fey in the popular culture of the day.”

Trudeau was an unlikely champion of youth culture with acne scars and thinning hair. He was 49 that year; Trudeau lied about his age in the Parliamentary Guide, writes Litt. “Trudeaumania” was coined as a dismissive putdown by conservative commentator Lubor Zink, a National Newspaper Award-winning columnist with the Toronto Telegram. Zink rated Trudeau “conceited, tactless, ruthless and dangerous,” and to his last days in the Parliamentary Press Gallery in 1995 maintained Trudeau was a Red.

Nor was all Canada agog for Trudeau in 1968. It took him four ballots to win the party leadership over Robert Winters, a corporate CEO. Trudeau never won 50 percent of the popular vote. The party lost eight seats in Atlantic ridings that year and 424,000 Canadians voted Social Credit, arch-foes of the hippie culture.

“Protest movements and the counterculture defined the Sixties because they ably exposed systemic injustice and establishment hypocrisy, were highly publicized by the media, and reflected the adolescent alienation of the rising baby boom generation,” notes Trudeaumania. “But only a small minority, even among the young, seriously challenged authority or lived the counterculture.”

But something did click in ’68, the first election in which boomers cast ballots. Trudeau was the first PM born in the 20th century. His contemporaries in Parliament were First War veterans in black Homburgs who campaigned with bagpipers. Trudeau by contrast entertained CBC-TV cameras by sliding down banisters in an era when the network monopolized a one-channel universe. Three million viewers a week watched Don Messer’s Jubilee. Trudeau by contrast was electrifying.

“It was television that first introduced Trudeau to the public, put him on the leadership radar screen with its coverage of his legal reforms, and made him a national celebrity,” writes Professor Litt; “Even as it unfolded, Trudeaumania was distinguished by a self-consciousness about the very process that enabled it. Contemporary commentators fretted terribly, regularly and publicly about whether the media were subverting the democratic process.”

One 1967 CBC-TV feature showed Trudeau “zipping around Ottawa in a sporty foreign convertible” with “an upbeat, jazzy soundtrack and shots of the Peace Tower off-kilter at a rakish forty-five-degree angle,” writes Litt. “The mod mode of presentation signaled this fresh face in cabinet was a trendy, ‘with it’ kind of guy, someone to keep an eye on.”

Nearly a generation after his death, Liberals still speak of the age of Trudeau. The facts are even better than the myth.

By Holly Doan

Trudeaumania, by Paul Litt; University of British Columbia Press; 424 pages; ISBN 9780-7748-34049; $39.95