Canadians don’t think of themselves as some of the most liberal people on earth, but we’re pretty close: gay marriage, nude theatre, cuss words in Parliament, no social aristocracy of any kind, and every liquor store has an ample parking lot.

When former Attorney General Vic Toews left his wife to take up with a younger woman he not only escaped shunning – Toews was appointed a judge – his friends said they were shocked, shocked anyone dare read Toews’ divorce papers, though they are public documents. This does not happen in America.

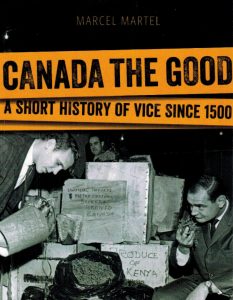

Our uniquely Canadian concept of liberty and vice is documented by Professor Marcel Martel of York University’s Department of History. Canada The Good is a sweep through three centuries of gambling, drinking and fornication. There emerges a kind of consensus that Canadians should be let alone to do what they want in the privacy of their homes.

When Parliament held an 1898 plebiscite on prohibition a majority voted to ban booze, and MPs promptly ignored the result. In Catholic Québec and New Brunswick, liquor was never much restricted. In Protestant Ontario and Alberta, dry laws were so successfully enforced the crime rate fell. It seemed everybody was happy.

“How should society prevent or reverse the disintegration of morality?” writes Martel. “Moral reformers considered various means for slowing down and hopefully reversing the degeneration process. Through their churches, they encouraged people to change their behaviour. According to Protestant morality, everyone should practice self-restraint.”

Martel’s research is delightful. Who is not wiser on knowing Canada’s first lottery was licensed in 1732, or that Confederation-era Halifax had 600 working prostitutes, or that Parliament’s 1869 Act Respecting Vagrants targeted any “night walker wandering in the fields…not giving a satisfactory account of themselves.” They just don’t write Acts like that anymore.

Canada The Good delves into the roots of much of the anti-vice law that persisted until cannabis was legalized in 2018. If the country maintained a “repressive anti-drug agenda”, as Martel puts it, the source dated from a 1908 debate in the House of Commons that resulted in Canada becoming one of the first countries to criminalize the sale of opium under threat of hard labour.

Also striking is how much of our historic campaign against wickedness reflects the character of one man, John Thompson, the justice minister who wrote the first Criminal Code in 1892. Professor Martel does not profile Thompson, though his story is documented elsewhere.

A rum-drinking Catholic with nine children and a hearty laugh, Thompson wrote the Code to reflect a world that long lingered in our criminal law. Alcohol was nobody’s business, homosexuality and birth control were outlawed, the public humiliation of stocks and pillories was abolished, and spanking children was okay if done in the home.

“The regulation of vice has changed over time,” notes Martel. “This should give us pause for reflection.”

By Holly Doan

Canada The Good: A Short History Of Vice Since 1500 by Marcel Martel; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 210 pages; ISBN 9781-5545-89470; $29.99