Catastrophes inspire art. Many an 18th century painter documented the Great Fire of London and eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Artists similarly tried to chronicle Canada’s one true catastrophe as described by the Truth & Reconciliation Commission. The results have been jarring. Arts of Engagement spreads the canvas.

From 1867 some 150,000 Indigenous children were forced through the Indian Residential School system. The Commission appointed to examine the historical record was the product of a class action lawsuit, designed by liability lawyers. The outcome satisfied almost no one.

“Truth-telling was not to include the naming of individuals and institutions associated with wrongdoing ‘unless such findings or information has already been established through legal proceedings,’” writes Prof. David Garneau, of the University of Regina. “Truths were to be accounts of subjective experience, feelings and perceptions rather than the relating of facts.”

The result: victims of child abuse were angered by public indifference; churches were baffled they as a group were classed as sadists; and the public was resentful all Canadians were to be shamed for historical crimes sanctioned by officialdom. When the Commission declined to name names, when everyone is to blame, nobody is to blame.

Prof. Garneau writes the confines of Commission hearings discouraged the most telling testimony: “Rage; the refusal to forgive; the naming of names; the details of intergenerational effects; the use of Indigenous people in these schools to oppress their own; the deformation of masculinity there; discussion of what happened to the payout money and how it distorts individuals, families and communities; the Metis who were also subjects of these places, and so on.”

Yet the Commission’s work was poignant enough to provoke artistic expression. This is the core of Arts of Engagement. It is plaintive and absorbing.

Co-editor Dylan Robinson, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Arts at Queen’s University, recounts one startling incident. At a 2012 hearing in Victoria where commissioners heard hours of tearful testimony on incidents of pedophilia and child cruelty, a local choir wrapped up the session with a song, Susan Aglukark’s O Siem. “I sat listening in disbelief,” Robinson writes.

“Fifty singers repeated the chorus, ‘O Siem, we are all family; O Siem, we’re all the same,’” Robinson recalls. It was supposed to make people feel better.

“To sing this song after three days where a history of inhumanity was overwhelmingly present felt both inappropriate and offensive,” says Robinson. “The irony in this song is, of course, that the history of abuse and cultural oppression in residential schools is anything but ‘the same’ as the education received by settler Canadians, nor are the present realities of Aboriginal communities and the settler Canadian public ‘the same.’”

Arts of Engagement cites another awkward incident at the National Gallery of Canada in 2011, where a visiting U.S. anthropologist delivered an oration on the meaning of the Residential School experience as expressed in art. The lecturer was white; his audience was Indigenous. “The crowd was sensitive to his lack of sensitivity,” Arts of Engagement notes. “The talk peaked with a comparison of the effects of Indian residential schools to flesh-eating disease, compete with photographs. It was offensive, particularly to the survivors present. Oblivious and confused, the man was ushered from the building.”

Interestingly, the failed lecturer inspired an oil painting Aboriginal Curatorial Collective Meeting. It depicts a series of colourful panels with empty speech bubbles. It fits.

By Holly Doan

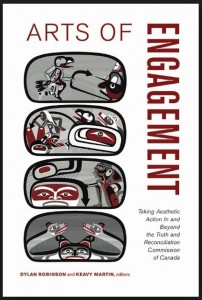

Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action In and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, edited by Dylan Robinson & Keavy Martin; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 382 pages; ISBN 9781-7711-21699; $29.99