Canadians’ embrace of conservation has come a long way since “back to nature” meant car camping with briquettes, and B.C. tourist films extolled carefree driving up the parkway to Fairmont Hot Springs.

Historian PearlAnn Reichwein of the University of Alberta cleverly documents this evolution through the viewfinder of the Alpine Club of Canada. Once a tea society for Anglophiles and dilettantes – no Jews were allowed for the first 40 years – the club over decades transformed itself into an advocate of conservation and protector of national parks. It was a long climb.

Canada does not see itself as an alpine nation though our mountain ranges are spectacular. The Alpine Club even today has fewer members (10,000) than Calgary’s Glencoe Golf & Country Club (12,000). Most Canadians have never seen the Rockies. Many consider them a backdrop for postcards. Few noticed when the 41st Parliament voted to allow an Alberta ski operator to expand into one national park, and ExxonMobil to conduct seismic tests in another.

Mountains carry no profound connection for Canadians as they do in, say, Germany, where mountaineering has long inspired a Wagnerian cult. From the earliest days of silent movies in the 1920s Berlin audiences thrilled to “a film genre which was exclusively German,” the mountain film, the “gospel of proud peaks and perilous ascents,” reviewer Siegfried Kracauer recalled in 1947. “Whoever saw them will remember the glittering white of glaciers against a sky dark in contrast, the magnificent play of clouds forming mountains above the mountains”.

And here? “Indifference,” writes Reichwein. Mountaineering was deemed an expensive and “foolhardy passion” and conservation an afterthought. Not until 1945 did Alpine Club members protest officialdom’s irritating habit of renaming mountains for political figures. “General Eisenhower is not a mountaineer,” the club complained when cabinet renamed Banff National Park’s Castle Mountain for the hero of Normandy. Not until 1969 did the Alpine Club newsletter caution members to beware of “the fragility of the natural environments in the face of increasing population and development pressures”.

The Alpine Club of Canada was established in mountain-free Winnipeg in 1906, closely modeled on an elite British club founded in 1857. This was no environmental group. Charter members and patrons included the president of the Canadian Bank of Commerce, the wife of the president of Burns Meats and a vice-president of the Canadian Pacific Railway which subsidized club activities for years as a way to draw paying customers to its Rocky Mountain hotels.

Membership dues were $300 a year, the equivalent of more than $6,400 today. Members attended campouts wearing neckties and moustache wax: “The Alpine Club of Canada was an English-speaking organization dominated by members who were urban, well-educated, leisured and drawn largely from professionals,” notes Climber’s Paradise. When the club organized its 1937 campout at Jasper Park’s Maligne Lake more than three tons of gear was hauled up by road, rail and horseback, including a tea tent.

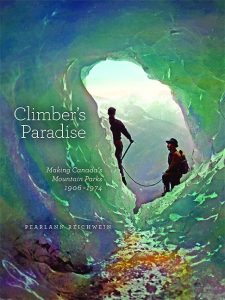

Reichwein notes that only with the affluence of postwar years did more Canadians begin to embrace the outdoors, not as an expression of “imperial conquest” but as something approaching a defining national characteristic. Climber’s Paradise draws readers along with intriguing anecdotes and beautiful photography, and an affectionate narrative of how more and more Canadians were inspired to look up.

By Holly Doan

Climber’s Paradise: Making Canada’s Mountain Parks, by PearlAnn Reichwein; University of Alberta Press; 390 pages; ISBN 9780-8886-46743; $45