The film classic It’s A Wonderful Life recounts the story of George Bailey, a frustrated everyman trapped in a small town with unfulfilled dreams of travel and adventure. But what if George left Bedford Falls? He’d have become Conrad Kain. It is a story too poignant for filmgoers. Instead it is a compelling title from University of Alberta Press.

Kain is renowned among Canadian mountaineers as a pioneering guide so accomplished they named a British Columbia peak for him, Mount Conrad. He escaped grinding poverty as a miner’s son in rural Austria and travelled the world from Honolulu to Ulaanbaatar.

“As far back as he could remember his ‘chief ambition was to travel,’” notes Letters From A Wandering Guide. “As a boy, despite the constraints of unremitting poverty, he never missed an opportunity to speak with tourists who passed through the alpine valleys near his home. ‘I would ask a great many questions,’ Kain wrote. ‘Where he came from, where intended going, what the place was like where he stopped last.’”

Hired by the CPR as a Rocky Mountain guide for wealthy tourists in 1908, Kain spent his life doing what he loved. On ascending every peak he would cry, “Bergheil!” – an Old Country greeting with no English equivalent, writes editor Zac Robinson: “It loosely translates to ‘salute the mountains.’”

Cue orchestra, roll credits. Hugs and tears all ‘round.

Not even close. Editor Robinson poured through Kain’s correspondence at the archives of the Alpine Club of Canada, a total 144 letters Conrad wrote to an Austrian pen-pal over 27 years. Here the wonderful life goes awry.

From the sunshine of youth Kain in turn becomes cynical, as so often occurs with those who work in the tourist trade, and expresses the bitterness of the new immigrant. Letters takes readers page by page through a man’s life and thoughts. It is a dark and absorbing narrative.

Kain grows resentful of the Americans he guides up and down Banff peaks. They are rich, and he earns $3 a day. He asks them to send souvenir photos and most never bother: “Such little things hurt you as a guide,” Kain writes. “One connects one’s life to the gentleman on the rope, goes first in all dangerous situations, is ready to risk one’s life for the gentleman, and the thank you is to deny you some little favour!”

“The injustice of the world with its money-hungry people makes so much impossible to achieve for most of us poor people,” Kain laments in 1915; “Sometimes I really cannot believe that my life should be a failure!”

Kain bemoans his beloved homeland, an Alpine paradise of pretty girls and “boys in lederhosen, bare-kneed, Tyrolean hats,” now overtaken by Jews, he writes in 1923: “I am sorry that the Jews got such a stranglehold in Austria.”

He dodges wartime military service and heads for the bush: “In the wild forest, I often cried. Tears shed from the eyes of a grown tough man are the most painful…Austria is MY HOME COUNTRY and I LOVE my mountains.”

In the end Kain grows resentful. He might have become a scientist, he grumbles, but instead wound up on a hardscrabble B.C. farm. “For the sick people and the poor, Canada is nothing. It is heartless!” he writes.

Readers discover in the end Kain was only truly happy with a climbing rope around his waist and an icepick in his hand. He died in 1934 and is buried in Cranbrook. His tombstone reads, “A Guide Of Great Spirit.”

And now we know what would have become of George Bailey if he’d ever left Bedford Falls.

By Holly Doan

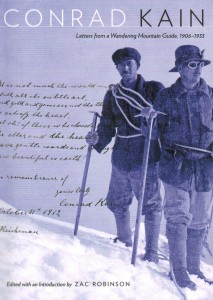

Conrad Kain: Letters From A Wandering Mountain Guide, 1906-1933; edited by Zac Robinson; University of Alberta Press; ISBN 9781-7721-20042; $34.95