Canadian history for generations of sufferers has been a tiresome recitation of patriotic themes sanctioned by officialdom: Champlain, Vimy, the CPR. There is so much more.

Among unsung benefactors are those researchers who seek out the hidden corners of Canadiana. For little reward and less acclaim, they devote thousands of unpaid hours in documenting the lives and trials of our ancestors. The results are gold. An example is African Canadians In Union Blue.

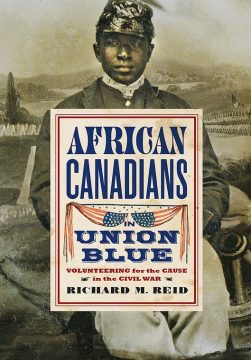

Professor Richard Reid of the University of Guelph documents the story of Afro-Canadians who enlisted in the greatest cataclysm of the 19th century, the U.S. Civil War. Reid is a gifted writer. His research is extraordinary. In 308 pages Reid convincingly challenges everything Canadians think they know about the era.

First, slave guilt. Whatever sins Canada must bear from our past, this isn’t one. Former Governor General Michaëlle Jean remarked in a 2008 speech, “Less than 200 years ago, thousands of men and women, African and Aboriginal, were subjected to abuse and torture by their owners. Slavery existed on Canadian soil.” Toronto Star columnist Royson James in a 2007 article They Need To Pay appealed for reparations for descendants of slaves in Canada, quoting one that “Canadians want to deny our complicity with the racist construction of North America.”

This overstates the case. African Canadians notes Upper Canada introduced an abolition law in 1793 fully 41 years before Britain abolished slavery. When Prince Edward Island passed its own Abolition Act in 1825 Reid notes it was purely symbolic: “There were no slaves on Prince Edward Island.”

Canada in 1861 had two black periodicals, the Voice of the Fugitive and Provincial Freeman. Reid tells the story of Shadrach Minkins, a fugitive slave who fled to Montréal in 1851, married an Irish woman and lived a long and prosperous life. When the Prince of Wales passed through Buxton, Ont. on tour in 1860, townspeople nominated a local black educator James Rapier to deliver the address of welcome: “Here we enjoy true freedom,” Rapier said.

“Public sympathy for African Americans in British North America was sufficiently great that some feared its exploitation by the unscrupulous,” writes Reid. “In 1841, Reverend R.V. Rogers warned readers of the Kingston Chronicle & Gazette ‘against the imposition of a coloured man who claims to be a runaway slave raising money to buy his child.’”

Then there is the mythology of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. While fugitive slaves undoubtedly fled north, Reid concludes their numbers were small. The overwhelming majority of Afro-Canadians were born and raised here, and as proud Nova Scotians and Ontarians as any neighbour.

“Of crucial importance is the fact that the numbers of fugitive slaves who could possibly have reached British North America are quite limited,” he notes. “Tales of flight and rescue, capture and triumph made for sensational reading in newspapers and published accounts, but only a thousand or fewer slaves successfully escaped their American owners each year, and most came from the Upper South.”

And then, the war.

Canadian officials were Confederate sympathizers. So many Confederates were welcomed in Windsor, Ont. that Lincoln contemplated border controls. Montréal was such a popular secessionist hangout that John Wilkes Booth spent time in the city, plotting the kidnapping and assassination of the U.S. president. In pre-Confederation Canada it was a felony to enlist in the Union Army, punishable by seven years’ imprisonment under the Foreign Enlistment Act.

Yet thousands of blacks enlisted anyway. Here African Canadians documents the extraordinary stories of ordinary sailors and infantrymen who volunteered under threat of arrest and a gruesome death abroad. Reid recounts the Fort Pillow Massacre, an 1864 atrocity in Tennessee in which black Union soldiers who surrendered to Confederate cavalry in Tennessee were disarmed, shot and mutilated.

So many Canadians black and white volunteered in the war the Grand Army of the Republic, a forerunner of the American Legion, later opened veterans’ branches in Manitoba, Ontario and Québec. Black volunteers numbered some 2,400 Reid estimates: “They shared not only a common purpose but a common set of values – courage, duty, service,” he writes.

Readers are left to wonder whatever became of the Williams Brothers of St. Catharines, Ont., Henry and Richard, who enlisted at 14, survived the war but vanished from the historical record in 1865, or John Weeks, 19, a cook from Chatham, Ont. who went missing in battle, or Samuel Sylvia, a Nova Scotia sailor who enlisted in New Hampshire where the state had no black regiments and was wounded in a vicious skirmish in South Carolina nine days after the South surrendered.

African Canadians In Union Blue recounts these veterans and their era and proves there is so much more to Canadiana than Champlain and the CPR.

By Holly Doan

African Canadians In Union Blue: Volunteering For The Cause In The Civil War by Richard Reid; University of British Columbia Press; 308 pages; ISBN 9780-7748-27461; $32.95