Environment Minister Catherine McKenna’s claims of climate change fatalities are contradicted by new data. McKenna repeatedly pointed to a surge in deaths in a July heat wave in Québec as proof of the need for a national carbon tax. Figures show the death rate in July was the same as last year.

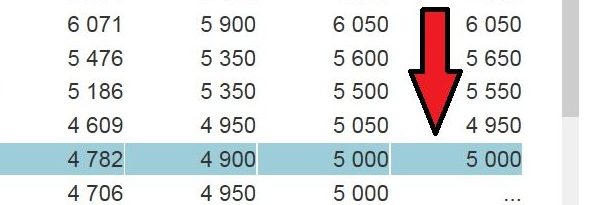

The Québec Institute of Statistics said deaths across the province for the month totaled 5000, the same as the identical period last year. Deaths for July were comparable to the ten-year average and below a peak of 5,072 deaths in July 2010, when average temperatures were two degrees cooler.

“The number of deaths in July is identical to last year’s estimate,” said Frédéric Payeur, a demographer with the Institute. “It is in fact a bit counter-intuitive since we heard about many heat wave-related deaths last summer. We will update this number tomorrow, but I don’t expect the new preliminary estimate to be much different.”

Final estimates will be completed by 2020, said Payeur. “We will need to look into precise causes of deaths for a proper estimate of heat wave deaths,” he said. “It is difficult. In these kind of deaths, causality is not straightforward.”

Various media reports last July claimed 93 “suspected deaths” in Québec including 53 in Montréal in a two-week period due to a heat wave. Media attributed figures to unnamed local authorities. No comparable figures were reported in Ontario though the same heat wave extended through the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River valley.

Environment Minister McKenna cited the deaths in promoting a 12¢-a litre carbon tax under the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act. “We are all paying the cost of extreme weather events like floods, like droughts, like forest fires, and 90 people died in Québec this summer because of extreme heat,” McKenna told the Commons on October 26.

“We’re seeing the impacts of climate change across the country, whether you live in the West, where you see these extreme forest fires; you live in the Prairies where you see droughts and flooding; or you live in the East, where you see extreme heat that’s literally killing people,” McKenna told reporters October 29. “We need to work together. We owe it to our kids.”

Environment Canada data show temperatures in Montréal were unmistakably higher this past July, though the number of deaths was not. Average daytime highs were 30° compared to 25° for the same period in 2017.

Overnight lows in July remained above 20° for 11 days, compared to 9 days for the same period last year. Québec’s Ministry of Health did not comment on the statistics.

“The Ministry entrusts the National Institute of Public Health of Québec with the mandate to produce an annual monitoring report on the impacts of extreme heat,” said Marie-Claude Lacasse, spokesperson for the ministry. “This report will be finalized at a later date.”

Canada’s deadliest heat wave occurred in Manitoba and Ontario in July 1936. Deaths numbered 1,180 by official estimate, including 400 drownings amid 40° temperatures. The 1936 heat wave forced factory shutdowns in Winnipeg, cooked fruit on the trees in Hamilton, buckled a Canadian Pacific Railway trestle at White River, Ont. and was blamed for 64 forest fires.

Health Canada in a 2018 study Qualitative Research On Health Professionals’ Awareness And Perceptions Of Heat Health Issues concluded that “extreme heat is not viewed as a major problem”. Doctors surveyed by department pollsters described heat-related deaths as “very rare” in Canada.

By Staff