Canadian diplomats feared Chinese troops would “invade” their embassy in Beijing in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, according to newly-released records. Dramatic Telex messages cabled by embassy staff back to Ottawa cite atrocities in the tumult after the mass shootings, including public executions and the retrieval of bodies from a Beijing canal.

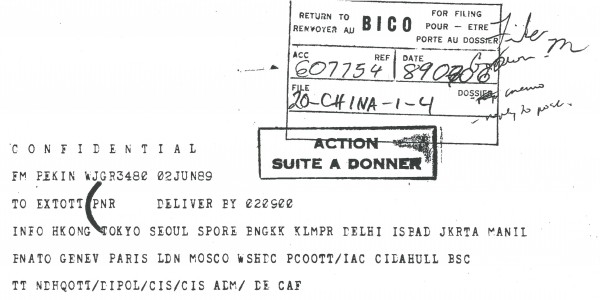

Telexes marked CONFIDENTIAL were released by Library & Archives Canada under Access To Information. The messages run to thousands of pages, documenting Beijing’s summer of upheaval 26 years ago as students massed in the central square and were shot by the People’s Liberation Army on June 4, 1989. The embassy described the killings as “savage”, recounting the eyewitness account of one survivor interviewed by diplomats.

“An old woman knelt in front of soldiers pleading for students; soldiers killed her,” the embassy reported; “A boy was seen trying to escape holding a woman with a 2-year old child in a stroller, and was run over by a tank”; “The tank turned around and mashed them up”; “Soldiers fired machine guns until the ammo ran out”. So many bullets were fired at Tiananmen “they ricocheted inside nearby houses, killing many residents,” the account continued.

“It may be years before the true story is known,” the embassy wrote; “The era of darkness may be long.”

In a June 7, 1989 message, diplomats wrote they were contacted by Chinese officials demanding to know if any dissidents had sought refuge in the embassy amid mass arrests of protestors. Staff estimated 10,000 people had been arrested in Beijing alone, including two employees of IBM who were jailed for sending faxes from the company’s office.

“They enquired whether the Canadian Embassy in Peking had been approached by Chinese students seeking asylum,” the Telex reads; “Officials are in a quandary how to respond as they fear that if the Embassy takes them in, soldiers could invade the premises and remove them.”

Earl Drake, then-Canadian ambassador to China, said he couldn’t recall sending the Telex, but noted cable traffic was high during the crisis. “I have no recollection of sending such a message, but there was so much going on at that time that others may have sent it without clearing it with me,” said Drake, 86, who retried to Vancouver after leaving the foreign ministry.

“In any event, the issue did not arise because no Chinese students asked for asylum with us,” Drake said. The Department of External Affairs did waive immigration regulations for ex-protestors with family in Canada.

“The country is now being controlled by a group of vicious elderly generals and the government is run by people who will blindly follow their orders. The situation looks grim at best,” the embassy wrote in a June 15 message.

Shots & Cheers

Canadian diplomats in secret cables condemned China’s Communist Party leadership as “octogenarian”, a “gerontocracy”, “bereft of any credible claim to legitimacy” and led by “Emperor Deng” – President Deng Xiaoping, then 85. Deng appeared “increasingly feeble”, the embassy wrote: “He is said to be lucid”. One Telex reads, “An Australian doctor who has talked to a physician friend of Deng’s urologist confirms that Deng has for some time been suffering from prostate cancer”; “Deng has been taking cortisone treatments, which accounts for his puffy face”; “This may induce periods of hyper-activity”.

In other messages, staff lamented the “astounding stories of corruption at the highest levels” in China: “The Swiss Ambassador, himself an ‘Old China Hand’, told us that over the past few months every member of the Politburo Standing Committee has approached him about transferring very significant amounts of money to Swiss bank accounts. For obvious reasons, he has urged us to guard this information with the utmost care”.

Diplomats reported to Ottawa that insider information became difficult to find following the massacre: “One of the unfortunate results of the current situation is an inability to talk to many former Chinese contacts who, if they have not already fled the country or are not under arrest, now prefer not to talk with foreigners,” reads an August 2 Telex.

The embassy continued to recount blood-curdling incidents. One evening in Beijing, staff reported a series of seven shots were heard from the city’s Agricultural Exhibition Hall: “Shots were spaced at one-minute intervals and followed by what appeared to be cheers from a throng of people” – suggesting public executions had taken place.

“They are now entering a period of vicious repression during which denunciations and fear of persecution will terrorize the population,” reads one note.

Another Telex reported bodies had been fished from a Beijing canal: “Unconfirmed reports indicate they were soldiers who had been garroted.” More than a thousand executions were rumoured to have taken place in the Chinese capital, though diplomats wrote: “It is impossible to confirm these figures.”

“The situation looks grim at best and potentially disastrous,” the embassy reported; “It was probably thought that the massacre of a few hundreds or thousands would convince the population not to pursue their protests. It seems to be working.”

“Chinese we talk to despair about the future of their country,” diplomats concluded.

Most of the Telexes are unsigned. Ambassador Drake in his 1999 Memoirs Of A Prairie Diplomat recounted the summer of 1989 as “the most dramatic events of my life”. The government evacuated 550 Canadians after the massacre; recalled Ambassador Drake; and initiated Mandarin-language broadcasts on Radio Canada International. Then-foreign minister Joe Clark condemned the shootings as “senseless” and “brutal”.

By Tom Korski