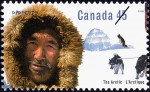

I shot my first caribou with a .22 rifle when I was seven years old. From childhood this sense of survival on the tundra was bred into us. We were given toy harpoons and snow knives as youngsters; my father once built a mock caribou out of snow and showed me how to stalk it.

Seven was a normal age for an Eskimo boy to harvest his first seal or caribou. Everybody trapped, and the fur trade was good business then. This was how Inuit families earned money for rifles and tea and flour. Culturally this was important for my family. They all joined in the meal from that first caribou I shot. I was very proud boy that day.

I was born in Chesterfield Inlet in the winter of 1950. We had no running water or store-bought clothes, and not everybody ate all the time. Our lives were consumed with hunting and fishing. Yet we were happy. We played like any other boys in the world.

The first English phrase I learned was from my father. I’d spoken Inuktitut at home. When Dad took me to the federal school in town when I was six, he told me: “If you see a white man, you say: ‘How are you?’” The school had a good library, and very good teachers.

This all ended when I was 12. When I reflect on this now, I ask myself – why am I an angry person? I trace it all back to my twelfth year. It was traumatic.

In 1962 there was a government push to take people from the land to settlements for schooling and “improvement.” The idea was that Inuit life was somehow defective, and had to be bettered.

I was considered a bright prospect so they sent me to a foster family in Ottawa. Here we had running water and store-bought clothes, bigger schools and libraries, supermarkets and suburbs. We learned to swim and play a musical instrument. We went to museums and the YMCA. I became a judo champion, and an outstanding student. In time I attended Carleton University with a degree in political science.

I tried not to forget Inuktitut, but it was very difficult as a boy.

And there was one other thing: my parents were never asked if they thought all of this was a good idea. They signed no consent forms. It was a matter of fact: a government agent said, “We’re taking you to Ottawa for a little experiment, wouldn’t you like that? Isn’t that great?” I don’t think Inuit were considered mature or worthy of being asked to consent to anything. The white men were in charge and Inuit were not. It was a matter of fact.

I did not know then how much I would grow to miss my family, and how lonely I would be.

When I reached 16, that’s when the real sense of alienation started. You are not really white, and not really Inuit; you are in between, or both – but never really accepted by either.

Many times I asked myself, why did the government do it?

I think they honestly believed their values as a middle-class, southern, industrial society were best for Inuit. It was as simple as that.

(Editor’s note: the author is former two-term MP for Nunatsiaq, Northwest Territories, and in 1979 became the first Inuit Canadian to win election to the House of Commons)