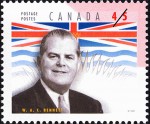

(Editor’s note: former British Columbia premier Bill Bennett died December 3 of Alzheimer’s, at 83. In his last interview, with Blacklock’s publisher Holly Doan on February 8, 2008, Bennett recalled his boyhood and legendary father W.A.C. Bennett, seven-term Social Credit premier. Following is a transcription of his candid remarks):

It’s been 29 years since my father passed away, yet there is nothing in British Columbia that he did not touch. I remember he used to have little motivational sayings he would recite every morning. I recall one of his favourites:

- “Somebody said it couldn’t be done

- But he, with a chuckle, replied

- ‘Maybe it couldn’t’ – but he wasn’t the one

- To do it until he tried.”

He taught us the value of work and commitment at a very young age. Everybody worked at our house. Each morning my parents posted notes on the wall – this was your day to do this chore or that. We all chipped in, washing dishes or bringing in the wood. The whole family had to work.

My father grew up very poor, in Albert County, New Brunswick. It was not an easy childhood. His father was a longshoreman who deserted the family. Dad was shy, and always kept this inner reserve – even when he had that famous smile that Canadians grew to know so well.

Dad worked from boyhood. He was homeschooled by an older sister and never had the chance to complete his secondary education, though later he took correspondence courses in sales and accounting. In Saint John he started as a clerk in a hardware store at $3 a week. It was a two-mile walk from home.

All his life my father was careful with money. As premier he was careful with the public’s money, too.

In the Bennett Hardware store in Kelowna, the whole family helped out. Once, my high school basketball team had a road game in Kamloops. This was a Saturday – my day to work in the store. I asked Dad if I could go. He said, “Can they win without you?” I paused. “I guess so.”

“Stay here and work,” he said. “That’s your job.”

I think he ran the province the same way. He recounted advice he gave his own cabinet after becoming premier in 1952: “I don’t want you to be cross-piling sawdust the way they do in Ottawa. I don’t want to see your desks cluttered with papers and you telling me how you’re working yourself to death. If you can’t get your work done by 5 o’clock in the evening, there’s something wrong.”

My father was not a complex or mysterious man. He was driven to succeed. Confidence does not begin to describe it.

One of my earliest memories is accompanying Dad to the 1938 Conservative national convention in Ottawa. He’d campaigned for Parliament early in his career, and said later if he’d won he would have been prime minister.

My father was a climber. He ran for a provincial Conservative nomination in 1937, and lost; then lost the Conservative leadership in 1946. He lost a federal byelection in 1948, and a federal Conservative nomination in 1949. His own party twice refused to give him a cabinet post. Dad simply would not quit.

His whole life was a determined effort to climb the ladder till he reached the top rung. In the end, of course, he reached it, and won seven elections as premier of British Columbia. Everything he did was for the people. That was his whole life.