I was born in a remote Newfoundland community, St. Bride’s, population 700, in 1964. Life then was bound with the fisheries. I remember the put-put sound of the make-and-brake engines in the little boats going out to sea, and feel of the kelp underfoot as we made our way down to the harbour in the morning.

There we’d watch the hustle and bustle of fishermen and the plant workers reaping the bounty of the sea. I remember the lads cutting out cod tongues. It was a proud way of life for our people.

St. Bride’s is in Placentia Bay, about 175 kilometers from St. John’s. We went to the city once a year. My father Walter and mother Julia were grocers. There were nine children in the Manning family. I married a fisherman’s daughter from St. Bride’s who had six brothers and six sisters.

Electricity did not come to our town until 1968. Then came television, one channel, the CBC. We didn’t have recreation centres or fast food restaurants, yet we thought we had it all.

Dad would drop us off out in the middle of Branch country on winter mornings each Saturday and we’d play pond hockey until sundown. We took our player names from the pros, and the only professional hockey players we knew played for the Canadiens or the Maple Leafs. Since my initials are F.M., I had to play as Frank Mahovlich. Later in the Senate I met Frank. He asked me if I’d played hockey. “Yes, but not like you,” I replied. My hockey sticks came out of a neighbour’s wood pile.

Children in St Bride’s left school in Grade 9 or 10 to work in the fishery with their parents. When I finished high school, half my classmates settled into the fishery. I left for Alberta at 17 to find work in Fort McMurray. When I came back for Christmas in 1981, there was talk around town that they might close the fishery. Nobody could have imagined what the future had in store for us back then.

First, the federal government announced a two-year cod moratorium in 1992. Even then, families could not grasp the impact. “Only two years,” they said. It would be tough, but we could struggle on. Reality sunk in by the third year. I remember the despair when the fish plant closed. Women cried and men were dazed.

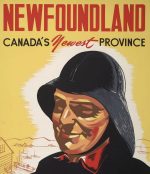

Was it the foreign trawlers that killed our fishery? Newfoundlanders started with hook and line, moved to gill nets, then cod traps. Canada entered into trade agreements that sacrificed our fish products in Newfoundland & Labrador to satisfy the auto industry in Ontario. When Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949, the fishery came under federal regulation. We could not have stopped it, but whichever government was in power, the livelihoods in St. Bride’s were never a pressing issue in Ottawa.

It is calculated that more than 70,000 people have left the bays and outports of Newfoundland & Labrador in the past 30 years. They took our town with them. Businesses closed, and the ancient traditions of passing our culture from fathers to sons is vanishing. St. Bride’s has only 250 residents left. The only school has 64 students, from kindergarten to Grade 12, including my daughter. I call it home, but few of my classmates remain.

When I returned from my first trip to New York City and we flew over The Rock and saw the beauty below, I realized why I am so attached to this place I call Home. I understand we cannot turn back the clock to the days of my boyhood. My children have left, too!

My oldest son lives in Harbour Breton, seven hours from home. I’m grateful he stayed in Newfoundland. My youngest boy is a folk musician in St. John’s. He tells the stories of our island and our people, and the land we left behind. He recorded a song entitled Salt In His Veins. That says it all.

(Editor’s note: Senator Manning’s commentary was originally published June 16, 2017)