I was born in Poland and emigrated to Canada with my family before the collapse of the Soviet Union. More recent emigres still return to Poland for vacations and family reunions. I have returned only once to meet my maternal grandfather, but I have no wish to reconnect with a place I left behind when my family escaped communist Poland.

We arrived in Montréal in 1983. My brother and I grew up there and went to Polish Saturday school where we learned Polish history and language. We learned about the First World War World and years of fascist dictatorship. We learned about the partition of Poland in the late 18th century and the series of revolts against different occupying administrations. The history lesson ended in 1945. Nobody talked about communism. Those were personal stories that were whispered at home.

Most Poles had similar anecdotes recounted from one generation to another – like the time my great-grandfather was beaten into paralysis by Soviet troops because he refused to give up his wedding ring; or that Russian soldiers robbed homes and hunted people: or when my grandfather hid in chicken coops to escape.

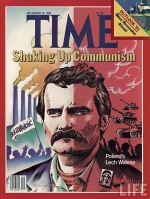

My father’s first job post-university was as a junior engineer at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk. After we left the shipyard became known around the world as the birthplace of successful Soviet resistance and for the leader of Solidanorsc, the Nobel laureate Lech Walesa. In my father’s day it was a mammoth industrial site that employed thousands of men and women and produced twenty vessels a year.

My father loved shipbuilding. He and his friends renovated a yacht and sailed all the way to Cuba, one of the few places Polish citizens were permitted to travel. My father hated communism but all workers were mandated by the Party to be a member of a Party-sanctioned union. It was never peaceful.

My father recalls rioting every May Day in his hometown of Katowice where they once burned the local Party headquarters to the ground. Then people at the Lenin Shipyard started moving away or just disappearing altogether. Some he would never see again. People thought the Soviets would send troops into Poland as they did in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Hungary in 1956. It was difficult to imagine an end to communism in Poland and nobody believed they would see the end of communism within their lifetime.

My family is very conservative but we hold sacred the right to vote. The first ballot cast by my brother and I was discussed around the dining room table. We talked about whether a government was good or bad. My parents cherished those conversations because we were free to have them. This shaped my family’s outlook on life. We were taught that Poles lost democracy because they did not cherish freedom enough.

It was a shock when the Soviet Union fell apart and Poland was suddenly free. But for families like ours it is as if all our memories and points of reference are embedded in the Soviet era. It was traumatic and terrible. Today when I speak with Canadians of Polish heritage who have emigrated since the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s like we have nothing to talk about.

When it comes to democracy, there’s a difference between theory and practice. Those Canadians of Polish heritage who survived that era learned lessons we cannot forget.

(Editor’s note: the author is Conservative MP for Calgary Shepard)