The National Gallery of Canada’s Serge Thériault, director of publishing and new media, was on the line. Blacklock’s asks: What is your acquisition policy on folk art please Pause. “Well, we don’t have a collection of folk art.” Pause. “What you consider folk art and what I consider folk art is probably not the same thing.”

The gallery’s Acquisitions Policy running to 16 pages decrees the national collection must reflect aesthetic qualities “of the highest possible nature.” No whirligigs. No macramé. Folk art gets no respect.

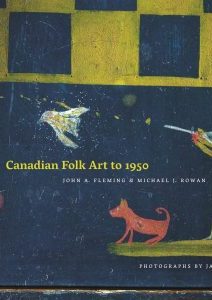

It is the squeezebox accordion of the Canadian art world, so ill-defined it’s confused with Christmas crafts or macaroni glued to a tin. “The term is unclear,” note authors John Fleming and Michael Rowan, and is hobbled by raw assumptions that folk art “is aesthetically unsatisfying”, “empty of any serious purpose or moral end”, “unimportant and even trivial” and “requires no formal training.”

Translation: Folk art is the expression of ordinary people with simple tools documenting familiar things, unashamedly and without being self-conscious. It is “the aesthetic of the everyday,” as Fleming & Rowan put it, which “asks nothing of us in return.” Canadians acknowledge the art form as worthy in others – the wood carvers of Bali, cave painters of New Mexico, or matryoshka doll makers of Russia – but rarely in ourselves.

Canadian Folk Art to 1950 attempts to balance the scale. It is a celebration. It spies the land on a simple mission: “To draw from the objects of everyday life their grandeur, mystery and magic, to represent the fantastic and hallucinatory related to the operations of the subconscious.”

If the results are crude, they’re joyful.

Here is a hooked rug with the image of a fat man, 1916. There are boxes and dressers, paper cuttings and cow portraits, stoneware jugs and model ships, a cigar store Indian and barber pole. Canadian Folk Art to 1950 devotes an entire chapter to 19th century trade signs like the shoemaker’s wooden boot that “punctuate urban spaces.”

And yes, there is even a whirligig, from New Hamburg, Ontario circa 1880. It depicts a militiaman in a snappy peaked cap. It would be magical in a stiff breeze.

By Holly Doan

Canadian Folk Art to 1950 by John Fleming & Michael Rowan, photographs by James Chambers; University of Alberta Press; 600 pages; ISBN 978-0-88864-556-2; $45