They don’t make British Columbia premiers like they used to. Richard McBride was the first to build his own navy, the first to create a university. “Any complaints?” he asked voters.

McBride was so sentimental that, when confronted by a petitioner with a son in the penitentiary – “He is only a boy, Mr. McBride, and meant no harm” – he gave the woman $20. He was a glad-handing spendthrift who cheerfully accepted a case of Old Curio Whiskey from lobbyists, and told British Columbians: “Let everyone wear a smile.”

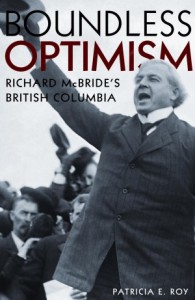

In Boundless Optimism biographer Patricia Roy captures the forgotten genius and sinfulness of this flawed man who campaigned by stagecoach, and ruled B.C. for three terms at the turn of the 20th century.

In McBride’s time the population of his province grew ten-fold. His life marked the opening of a territory vast as an empire, with timber, coal and peach orchards.

If B.C. was big, then bigness was a criterion for the premiership. McBride fit.

“I am always devoted to the interests of British Columbia, first, last and always and all the time,” he said in 1908. A Toronto Telegram reporter assigned to cover the premier’s speeches recounted, “When you’ve done shouting, ‘Be loyal to the party,’ and, ‘if you can’t boost don’t knock,’ you have all he said in half an hour.”

Of course there was more. Author Roy, professor emerita of history at the University of Victoria, documents the premier who was as hard-driving as the era.

He created the University of British Columbia in 1908, and in 1915 bought his own navy – two U.S.-built submarines. Without them, McBride told the legislature, “Vancouver and Victoria would have been subjected to a bombardment by German warships.”

McBride was a Conservative of contradictions. He had a Chinese cook but cursed Asian immigration; “Nothing would be left undone to make British Columbia a white man’s country,” he said.

McBride had six daughters but opposed votes for women, and restricted his wife to the sole function of wearing pretty gowns at tea parties. He was an attorney and real estate speculator, but could not balance a cheque book and left his own province nearly bankrupt. “He was a poor financial manager,” notes Roy.

McBride was never prosecuted for corruption, yet prospered as if by miracle. He never earned more than $10,000 a year as premier, yet rode in a chauffeured $3,000 Cadillac, sent his daughters to private schools and hired a household staff. When visiting London, he rang up a $620 bill at the Savoy hotel – the equivalent of $13,000 today.

“McBride’s enemies alleged that he had acquired an immense ‘fortune’ by ‘mysterious’ means, but there is no evidence of this apart from some ‘perks,’” Roy concludes.

The McBride era is vanished in B.C.; voters today expect honesty and financial competence. Yet, to read Boundless Optimism is to relive the gaslight era when the land was young, and rogues were tolerated.

By Holly Doan

Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia by Patricia Roy; University of B.C. Press; 428 pages; ISBN 978077-4823-890; $32.95