If you were inventing parliament, it would not look like the Texas hold ‘em version we have now: a rectangle chamber of adversaries seated face-to-face, seeking advantage on winner-takes-all. This is the product of “critical thinking”, writes Patrick Finn: “A mode of thinking that is governed by a critical approach to all incoming information that has winners and losers.”

“Our system of government is based on a form of critical thinking first established in ancient Greece,” explains Finn, associate professor at the University of Calgary’s School for Creative & Performing Arts. “Does anyone think it is still working? Or are we continually asking ourselves why this system will not allow us to work together more effectively?”

The record of the 41st Parliament speaks for itself. Legislators abolished the penny; renamed the Museum of Civilization; and debated a bill condemning the shooting of police dogs. This is not heavy lifting.

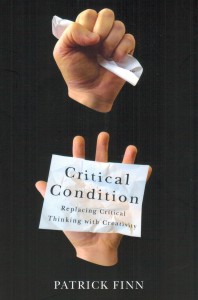

Critical Condition is a delightful and engaging book that challenges the very premise of Parliament, the courts, universities, you name it – the school of “us-versus-them thinking”, as Finn puts it. He cites the practice as pointless, unproductive, suspicious and mean: “No matter how we disguise it, it reeks of violence.”

“I admit to having enjoyed a few victories of this type myself,” Finn writes. “In one of my lowest academic moments, I once made a fellow student weep and run out of the room when I savaged him for ridiculing the work of James Joyce.”

Critical Condition proposes instead “loving thinking”, a keenly practical alternative despite the moniker that comes with a kick-me sign. It is a consultative system that invites creative problem-solving broadly applied to a unique problem. This is precisely how Canada helped win World War Two, and why townspeople sandbag riverbanks in flood season. No name-calling; no point-scoring; no matter who takes the credit.

“If our leaders were educated to believe that solutions were the goal, and not attacks, defences and victories, then they would be predisposed to find ways to act,” Finn writes. “If we trained all students to view critical quagmires as negligence, then our negotiators would no longer begin with lists of non-negotiable items. Creativity makes no room for the non-negotiable. Great ideas require no protection other than the room to breathe and the right to live.”

So, Parliament cannot solve the big problems, and instead quibbles over little ones. Critical Condition concludes the entire premise should be subjected to the same scrutiny it applies to trivialities. “The dictates of critical thought actually require us to question assumptions,” Finn says. “How interesting, then, that we are not allowed to question the system that commands us to question. Politicians often speak of issues that will kill a campaign as ‘the third rail’. They are referencing the power rail of the subway or train that kills on contact. How did we arrive at a place where critical thought has become the third rail of intellectual life? How did it become this strong?”

“If we want to compete, why not get serious about our competition?” Finn continues. “Let us compete against cancer, against pollution, against civil war, against domestic violence, against poverty.”

Or, we could elect a Parliament and have little to show for it but abolition of the penny and a bill on shooting police dogs.

By Holly Doan

Critical Condition: Replacing Critical Thinking With Creativity, by Patrick Finn; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 117 pages; ISBN 9781-77112-1576; $14.99