Few authors possess the skill to take an everyday image and turn it just slightly, in Twilight Zone fashion, to reveal a startling and intriguing truth. Professor Joan Sangster of Trent University does just that in The Iconic North. To read Sangster’s account is to question every common media depiction of the Arctic.

“The North has been rendered exotic, romantic, terrifying, sublime, enigmatic, otherworldly and intrinsically Canadian, and some of these adjectives are equated not just with the landscape but with the original inhabitants of the North,” Sangster writes.

This is not ancient history. Parks Canada’s fetishism with English exploration in the Arctic has cost taxpayers more than $21.5 million to date. “Recent politically orchestrated announcements and attendant media hoopla concerning the discovery of Sir John Franklin’s shipwreck in the Arctic are a salient reminder that we need an ongoing critical analysis of a romanticized North ‘discovered’ by white explorers,” says Sangster.

The Franklin Expedition was a famous failure of no scientific or exploratory value whatsoever. Media’s fascination with the pointless deaths of European sailors is striking. Millennia-old culture of Inuit is not documentary material in itself; it’s the fact 129 Englishmen froze to death that justified CBC-TV specials secretly subsidized with a $98,000 Parks Canada grant. “Fantastic media coverage,” the agency enthused.

Iconic North challenges the narrative. Implicit in Arctic imagery in most TV documentaries, newspaper features and school textbooks is the suggestion history began with inhabitants’ contact with whites. Sangster calls it a “European ‘obsession’ with the romanticized image of stoic but happy Inuit facing environmental adversity with unending cheerfulness.” The propaganda is not harmless. “These images thus helped to sustain Canada’s distinctive brand of internal colonialism,” she notes.

Iconic North is meticulously researched. Sangster has a matter-of-fact writing style. In 400 devastating pages she makes the case our popularized conceptions of the Arctic are Eurocentric, condescending and inaccurate, “constantly invoked in the mainstream media as Canada’s last frontier – one where settlers and Indigenous peoples were engaged in constructing new relationships in contrast to the old, tattered antagonism of southern Indian and white.”

Sangster examines RCMP, a short-lived 1959 CBC cop drama that depicted the exploits of Jacques Gagnier, a “paternal and benevolent” Mountie in the fictional town of Schamattawa “bringing insight, law and justice to bear on Indigenous peoples and their problems.” In one episode Constable Gagnier saves a whole village of children from gun-toting hostage takers “while their Aboriginal parents stand by, cowed into fearful acquiescence”. Producers and viewers alike took it for granted that Indigenous parents were too weak or inept to care for their own children

Sangster also recounts I Was No Lady: I Followed The Call Of The Wild published by Ryerson Press, the 1959 memoirs of Jean Godsell, Scottish-born wife of a Hudson’s Bay manager. Godsell has trouble with an Inuit houseboy she calls Johnny, and recalls “sage advice” from her husband: “‘He’s just trying you out,’ he remarked, ‘he wants to see how far he can go with you. It’s a typical Indian trick. Give him hell,’ he reiterated, ‘if you don’t master him now, you never will.’ Never will I forget the look of stupefaction on John’s face when I finally sailed into him…From then on, on my husband’s advice, I gave him what-for on an average of once a month. Often I had to make an excuse for doing so. At first this seemed rather mean but I soon learned, as everyone does who handles Indians, that it was the only way to keep him in line.”

No Mississippi planter ever put it more succinctly.

By Holly Doan

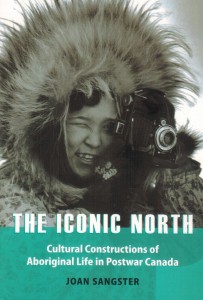

The Iconic North: Cultural Constructions of Aboriginal Life in Postwar Canada, by Joan Sangster; University of British Columbia Press; 400 pages; ISBN 9780-7748-31840; $34.95