On February 6, 1940 Governor General John Buchan collapsed in his bathroom at Rideau Hall. Buchan had suffered a paralytic stroke and fractured his skull in the fall. He lay on the tiled floor for an hour before they found him. He was dead in a week.

Buchan had been a celebrity novelist. The same year he came to Ottawa in 1935, Alfred Hitchcock released a film adaptation of Buchan’s thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps. It was like appointing John Grisham governor general.

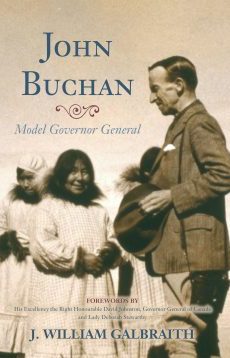

Despite his international fame and sudden death Buchan today is forgotten, almost as if his service in Canada was expunged from the record. The reason is revealed in J. William Galbraith’s biography.

Buchan was a Nazi appeaser. He failed the greatest moral test of his era and was capable of “dangerous rationalization,” writes Galbraith. In a November 11, 1938 speech to a Canadian Legion banquet the Governor General suggested Hitler might use British veterans as peacekeepers in Nazi-occupied territories. “The defense of a country is always a difficult question,” he said. “You dare not neglect it or you may be taken at a sudden disadvantage. But it is possible to overdo it and thereby increase the very risk which it was intended to prevent.”

Buchan’s speech came two days after Kristallnacht, the 1938 pogrom that saw German synagogues burned and Jews murdered in the streets. The Governor General did not mention it. “All defence carries a face of war,” he said.

John Buchan: Model Governor General is no gotcha biography. Galbraith is a member of the John Buchan Society. He does not mention the Kristallnacht speech. Instead he celebrates Buchan as the man who adapted his ceremonial office into a kind of national greeter who toured the Arctic, patting cattle at livestock shows and giving speeches on the CBC. Readers will note how little the job has changed.

Galbraith is an honest biographer who provides a first glimpse into Buchan’s enthusiastic appeasement of the pre-war Nazi regime. Germany’s occupation of Austria was “very largely our own blame,” said Buchan. Press critics of Neville Chamberlain were “donkeys”; Winston Churchill “exasperated everybody”.

Appeasers fascinate historians. How could they have been so wrong? Buchan and his crowd feared Nazis. They appeared paralyzed by post-traumatic memories of the First World War and were unmoved by the Germans’ early victims: communists, trade unionists, Slavs, Jews – though Buchan was hardly anti-Semitic, his biographer notes. The Governor General’s wife was a supporter of Montreal’s Hadassah. “No man is so strong as he who is not afraid to be called weak,” Buchan wrote in 1938.

When war came Buchan sent his own two sons into the Canadian Army, but his stroke saved him the agony of witnessing the full tragedy of 1930s politics. Buchan did not live to see the fall of Hong Kong and Singapore or the Blitz, the Holocaust or loss of empire that left Britain so broke it kept rationing food till 1955.

“My work here is over,” Buchan wrote at war’s outbreak. It was, in more ways than one.

By Holly Doan

John Buchan: Model Governor General by J. William Galbraith; Dundurn; 544 pages; ISBN 9781-4597-09379; $40 hardcover