It was a popular quip in the 1980s that West Edmonton Mall’s waterpark had more submarines than the Royal Canadian Navy. The sub service was always the heartbreak branch of the military: underfunded, ill-equipped, with working conditions that would be intolerable in a federal prison.

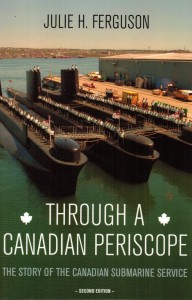

Author Julie Ferguson spent decades researching this affectionate tribute to the nation’s hard-luck submariners. It remains an intriguing and little-known story. It is also a mystery why anyone ever volunteered for submarine duty in the first place.

Modern underwater warfare dates from 1863 when the Confederate navy launched a combat submarine in Alabama’s Mobile Bay, the H.L. Hunley: a ten-metre tube with hand-cranked propeller and lighting by candle. The idea was to sneak up on Union warships dragging a canister of gunpowder in tow. Instead the Hunley sank like a stone. Rescuers later recovered corpses of crewmen huddled together clutching candles, their faces frozen in agony: “The spectacle was ghastly.”

Early Canadian submariners escaped the Hunley’s fate but the birth of the service was marked by awful conditions and failed equipment. In 1914 the B.C. cabinet, acting on false rumours that German cruisers were headed for Victoria, bought two diesel-electric boats sitting in a Seattle shipyard. The subs had been contracted to the Chilean government. B.C. was charged $1.2 million for the pair, three times what Chile paid. The Iquique and Antofagasta were unimaginatively renamed CC1 and CC2 and assigned to imperial service. It was not an auspicious beginning.

“Early submarines had no air purification, heating or cooling systems, and when they were submerged the air quickly became fetid and damp,” writes Ferguson. The vessels had a top speed of 18 kilometres an hour underwater but only for a few minutes. The wiring shorted in humidity and salt water contaminated the batteries, filling the subs with chlorine gas. On CC1 and CC2’s one epic voyage from Esquimalt, B.C. to Halifax via the Panama Canal the temperature in the engine rooms hit 60° Celsius and the vessels rolled so badly the crew became seasick.

Neither CC1 nor CC2 ever saw combat. The submarine jinx was set.

“If they had been asked, the submariners would have told the policy-makers that submarines were first and foremost weapons of enormous strategic power,” writes Ferguson. “Even the suspicion that one might be lurking outside a naval base was sufficient to bottle up a battle fleet.”

Instead submarines were cast as expensive and pointless. Even in the 1950s when defence spending peaked at nearly half the federal budget, the sub service was starved. When cabinet ordered new vessels in 1964, the Oberon-class Ojibwa, Onondaga and Okanagan, all three diesel-electrics were obsolete in the age of nuclear-powered craft. When Prime Minister Jean Chretien authorized the purchase of four more diesel-powered craft from Britain in 1995, one caught fire killing a crewman while repairs and refits to the fleet sent the program more than $700 million over-budget.

The heartbreak continues.

By Holly Doan

Through A Canadian Periscope: The Story Of The Canadian Submarine Service, by Julie Ferguson, Dundurn Press; 424 pages; ISBN 9781-4597-10559; $26.99