In 1918 the Imperial War Graves Commission enacted two notable regulations. All dead were to be buried with their units, regardless of rank, near the spot where they fell. And all families of the dead could submit personal messages, to 66 characters, to be carved into kin’s headstones.

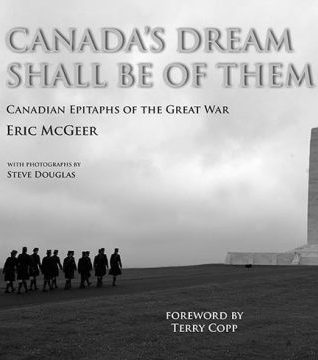

The effect was profound: mammoth, manicured battlefield cemeteries with indelible inscriptions. Wilfrid Laurier University Press asks, what did they write? Epitaphs were thoughtful, angry, ironic. They are collected in Canada’s Dream Shall Be Of Them. It is a beautiful, elegant book that will bring a reader to tears.

The epitaphs “were contributed not by the poets or artists we tend to associate with the Great War and modern memory, but by ordinary men and women,” writes Toronto historian Eric McGeer; “They are a window into another world, not a mirror to our own.”

The book is comprised of startling imagery by photographer Steve Douglas and McGeer’s crisp narrative. “Of the identified graves, just under half carry a personal inscription, many of which repeat formulae (‘Rest in peace’, ‘Gone but not forgotten’, ‘Son of…’) of little more than fleeting interest,” writes McGeer. “The number of inscriptions that offer insight into the minds of the bereaved, individually and collectively, comes to about 3,000,” approximately five percent of Canada’s war dead.

Headstone inscriptions were vetted – the Graves Commission reserved “absolute power of rejection or acceptance” on all submissions – though Commonwealth families were given latitude for personal expression. “Shot at dawn. One of the first to enlist. A worthy son of his father,” reads the epitaph of a British soldier executed for desertion. “Another life lost, hearts broken, for what?” says an Australian’s grave.

Canadian inscriptions expressed pride and loss. “Tell my mother I will meet her at the fountain,” reads the gravestone of Private William Rankin of the Royal Canadian Regiment, killed at age 17. “Frank! Jesus calls,” wrote the father of a private killed at 20. Other Canadian families wrote:

- • “An actor by profession. His last role. The noblest ever played”;

- • “He would give his dinner to a hungry dog and go without himself”;

- • “Last words to his comrade: ‘Go on. I’ll manage,” for a 21-year old private shot at Vimy;

- • “Just a high school boy, but a real man,” at the grave of a 19-year old;

- • “Enlisted voluntarily,” for a teenage francophone, in a curse on conscripts;

- • “It is finished,” on the headstone of a driver who died of wounds four days after the Armistice.

Most haunting is the fact few Canadian families would ever their see their hero’s grave. The epitaphs were written for posterity, not personal closure. “The only child of aged parents,” wrote the mother of a 16-year old private killed with the 58th Battalion. The family in six words described the end of the world in faraway France.

Canada’s Dream Shall Be of Them is stunning.

By Holly Doan

Canada’s Dream Shall Be of Them: Canadian Epitaphs of the Great War, by Eric McGeer; photos by Steve Douglas; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 224 pages; ISBN 9781-77112-3105; $49.99