After the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, Sitting Bull led the Sioux into southern Manitoba to escape reprisal by the U.S. cavalry. They wintered near my hometown. This went unmentioned in history class. We were told instead to memorize the travels of Champlain who didn’t come within 1,600 kilometres of Manitoba. Relevancy was irrelevant. “Curriculum is ideological,” as Prof. Dwayne Donald of the University of Alberta puts it.

“Official curriculum ideologies become so pervasive and unquestioned that their followers are left unable to recognize them as cultural and ideological,” writes Donald. He calls this “curricular worship.”

“Curriculum documents, and the educational priorities they emphasize, are thoroughly imbued with the cultural assumptions and prejudices that the majority of the members of the society have come to consider normal and necessary for young people to know and understand,” Donald explains in a tidy and devastating critique. “In teleological terms then, curricula can be understood as preparing children for a future that has been imagined on their behalf by adults. Thus, curricula are basically an exercise in citizenship, and the success of this exercise is generally assessed according to how well the children have taken on the characteristics that the adults hoped they would.”

Indigenous Education documents the uphill battle against stand-pat public schooling. Anyone who stepped foot in a classroom as student or parent will find common ground with these eloquent critics. The main Indigenous difference is the appalling cost.

“The costs of the current Eurocentric-based education system have been socially astronomical as evidenced by well-documented issues such as suicides, chronic underachievement and the high dropout rates of Indigenous children,” writes Prof. Sandra Styres of the University of Toronto. “By 1996 only twelve percent of Indigenous youth completed high school.”

Indigenous Education notes this is not a Canadian phenomenon. Hawaii did not establish Hawaiian-language immersion preschools until 1984. New Zealander Dr. Margaret Maka recalls as a student in the 1960s she won a high school prize as Most Promising Maori Pupil. There was no prize for Most Promising Anglo Student. That would be condescending and ridiculous.

“Maori teenagers are more likely to drop out of high school without qualifications and have one of the highest suicide rates in the world,” writes Maaka. “Our adults are overrepresented in prisons, have the poorest health records and are underrepresented as students and faculty in higher education. Chronic homelessness is a Maori phenomenon. Thus, it appears that upward mobility through the public school hegemony of things English at the expense of things Maori is a myth.”

By Holly Doan

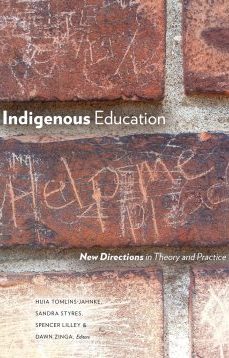

Indigenous Education: New Directions in Theory and Practice; edited by Huia Tomlins-Jahnke, Sandra Styres, Spencer Lilley and Dawn Zinga; University of Alberta Press; 560 pages; ISBN 9781-77212-4149; $45.99