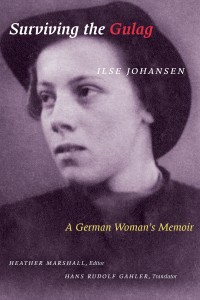

The Second World War altered a quarter billion lives. The number of eyewitnesses dwindles. We are left with personal accounts of ordinary people who saw extraordinary things. Surviving The Gulag is one.

Ilse Johansen in postwar years worked as a school janitor and cruise ship stewardess in Vancouver. Friends recall she seemed friendly enough but could not bear to throw out even scraps of food. Johansen wrote her memoirs, translated here from the original German. Surviving the Gulag is like pulling a loose thread that slowly unravels a tightly-knit narrative leading to unexpected places.

Johansen at first glance is not a sympathetic character. She was a German nationalist with an office job in Romania and a Nazi membership pin. “She herself wore the uniform of the Nazi Party for her civilian duties as a secretary in Bucharest,” writes editor Heather Marshall of the University of Alberta.

Johansen’s memoirs initially are laced with tedious commentaries on German superiority. Romanians are hapless, Russians are alcoholic brutes, so-and-so is remembered only as a Jewess. It is jarring to a 21st century reader.

Yet Johansen was also a skilled diarist who matter-of-factly recounts stark anecdotes of her arrest and detention after Bucharest fell to the Soviets in 1944. She recalls one inmate weeping from hunger and others fighting over fish bones. “Johansen was a careful observer of everything that happened to her and of the people with whom she came into contact,” notes Surviving the Gulag.

“Very few people lived through five years in a Soviet prisoner of war camp and managed to bring back notes and memories with as much factual information. She makes little attempt to explain or analyze, which gives the memoir the feel of pure and immediate observation.”

Johansen survives her war by stealing potatoes at a prison farm. She recalls the Soviet propaganda slogans urging inmates to meet their production quota: Remember 125%. She remembers, too, the descent into madness.

“Child mortality is very high in the camp,” she writes. One bunk mate, 22, has a toddler she keeps alive only for the sake of rations: “I have never seen a mother like this,” writes Johansen. “It is pitiful to watch this. She doesn’t send the child to the kindergarten because then she will not receive the child’s ration. Instead she lets the child sit on the bed while she is at work. The little one is so quiet that one can leave her alone. On these occasions it happens of course that she wets the bed. The little one begins to shake when she sees the mother enter the door. The woman is merciless; she beats and throws the child back and forth until we cannot watch it any longer. The poor little mite finally dies.”

Johansen survives beatings, a failed escape attempt and starvation, all amid the spectacular beauty of Russia. “Sky-high pines look up from deep gorges,” she writes. “Huge boulders are covered with wild roses”; “I feel lighthearted,” says Johansen. “Could this country be so cruel and terrible when nature is so gorgeous?”

In time Johansen even gains insight into her tormentors. Where Soviets once seemed subhuman, she learns: “Prison is an everyday reality for Russians. One can be a very decent person but have a history of having done time for several years. They are not ashamed of talking about it: ‘My mother is sitting in jail; my husband has been convicted and was given three years in the penitentiary.’ Nobody is surprised about it. Many times the reason is an injudicious statement reported by someone. Sometimes it is homicide. They talk about it as if it were nothing special. Life here is hard and people are formed accordingly.”

Johansen was released in 1949 – “no one seems to know why,” writes Editor Marshall – and immigrated to Western Canada. Surviving the Gulag leaves much unsaid. What remains is absorbing, and very human.

By Holly Doan

Surviving the Gulag: A German Woman’s Memoir, by Ilse Johansen; University of Alberta Press; 296 pages; ISBN 9781-7721-20387; $34.95