Police were not infrequent visitors to author Cheri DiNovo’s childhood home. All families have troubles but DiNovo’s make Angela’s Ashes look like a holiday camp. “I grew up in a violent, neurotic, narcissistic household where victims of their own personal traumas acted out in nasty, aggressive ways,” she writes. “This is not to blame any of them.”

Take Uncle Ken, one of the more responsible adults in the home. “It was Ken who took me to dance classes, Ken who took us shopping, Ken who drove us up to the family cottage and stayed with us there, Ken who financially supported us, Ken who always arrived at breakfast at the same time,” writes DiNovo.

“My breakfast was Sugar Crisp, white toast and milk. His, brown toast and coffee. It was also Ken who, one day as I was slurping down my second bowl of cereal, picked up a knife and slashed my Aunt Lorna across the neck.”

She ran away at 15 and sold LSD. “We assumed we would die young,” she writes.

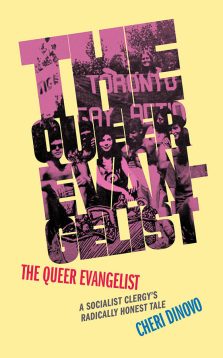

DiNovo is a United Church minister and retired New Democrat member of the Ontario legislature. Her memoir The Queer Evangelist: A Socialist Clergy’s Radically Honest Tale recounts a world of Trotskyites, crusading pastors, Bay Street stock jobbers and colourful Damon Runyon street people that exists in a surprisingly small geographical space, a few square blocks of downtown Toronto. It is unrecognizable seven miles away in North York, let alone Revelstoke or Mount Pearl.

DiNovo makes it work because she is a gifted writer with a wry sense of humour. She boasts she was one of the few in her Trotsky study club who actually read Das Kapital, later drove a Lada and is still capable of pronouncing, “Capitalism is a sort of money addiction.”

“It’s a fabrication that capitalism thrives on competition,” she writes. “It doesn’t. It thrives on consolidation. The rich get richer. The poor get poorer. The middle class empties out.”

“Capitalism was doomed,” she writes. Just as this begins to get tiresome, DiNovo recalls meeting a group of rich capitalist farmers among her rural congregation in Brucefield, Ont.

“I once asked my Bible study group why farmers worked so hard when they were sitting on so much land,” she recalls. “‘Why not sell most of it and retire? Buy a BMW and live in Florida?’ The women in the group looked at each other as if they’d never heard of such a thing and answered, ‘Then what would we do?’”

DiNovo served four terms in the legislature, becoming Party whip and caucus chair. Here, too, she writes with candour and irony. “The painful meetings are not with constituents whose problems the staff can handily solve, nor are they the ones where a bill or motion might draw attention to a serious political issue. The difficult ones are those you can see coming, where the constituent arrives with large binders, colour-coded inserts and briefcases full of paper. Inevitably their issues have something to do with a long saga of injustice, often genuine, at the hands of some bureaucracy or ministry.”

“These situations are usually very real and very hopeless,” she writes. “Our standard responses would be along the lines of ‘You’ve learned there’s very little justice in the justice system,’ or ‘You’ve learned there’s very little housing in the housing system.’ It always put me in mind of a scene in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina where people sleep outside bureaucrats’ doors waiting for a chance to be seen disdainfully for a minute or two.”

The Queer Evangelist is raw, a startling autobiography for a public office holder.

By Holly Doan

The Queer Evangelist: A Socialist Clergy’s Radically Honest Tale, by Cheri DiNovo; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 250 pages; ISBN 9781-7711-24898; $23.99