Working animals were once a staple of town and country life: pit ponies, sheep herders, warehouse mousers. All lesser mammals were bred for chores or meat. “The main thing to remember,” says a friend who’s spend a lifetime with horses, “is that they don’t care about your feelings.”

With automation and a declining birth rate, animals have become members of the family. As author Dave Olesen puts it, “In a culture that is becoming almost completely unfamiliar with animals as working partners, many people take up their dogs as little furry surrogate children.”

The few working animals left are the prima donnas of police service; when a Toronto police horse was run over by a car in 2006, they actually held a funeral. Ontario’s lieutenant governor attended. “Tears streamed down the faces of men and women,” the Montreal Gazette reported. No irony was noted.

“To watch huskies scrap with each other, or to watch dogs go after a teammate who has for some reason become a scapegoat, is sobering to anyone who tries to mold dogs to a human model or to elevate them to a preconceived notion of furry nobility,” Olesen writes. “They are physical, and we must relate to them on that level.”

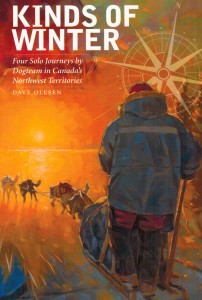

Kinds Of Winter documents Olesen’s treks by dog sled in the Northwest Territories. Even First Nations don’t use dogs anymore, but Olesen sought the Arctic experience as only an outsider can appreciate. He is from Illinois.

The result is a lively account of working animals in an unforgiving landscape. Olesen runs his dogs for miles and rests them in snow in -40°. “No one leaps to lick my face when I come down the line,” he writes. “I am the Alpha animal”; “I am also provider: of food, of a trail to follow in deep soft snow, of decisions and directions, of spruce boughs for bedding and salve for sore feet.”

Olesen does not name his dogs with adjectives: there is no Snowy or Fluffy or Skippy. The harsh climate causes some dogs to lose fur on their shanks, a painful condition known as “chicken legs”. The huskies eat fat and kibble. They run and fight and die; no funerals.

He praises one frankly vicious dog, Tugboat, a wheel dog that runs closest to the sled: “The wheelers often bear the brunt of heavy work in tight quarters, because the weight of the sled is forever jerking them from behind while the momentum of the team pulls them forward.”

“Tugboat was an exemplary wheel dog, brutish and strong,” he writes. The huskie was “a thoroughly unlikeable fellow, ever first to steal another dog’s supper or to instigate an utterly pointless brawl, all but blank in his relations with the human race”.

Kinds Of Winter is rare documentation of the few working animals that remain, in an Arctic region so forgotten Olesen notes they don’t even put out forest fires anymore: “No attempt is made to put them out for the country is far beyond any of the marked ‘values at risk’: cabins, fuel caches, fishing lodges, known grave sites.”

Olesen’s book is a crisp account of a world now gone in urban Canada, when animals worked as hard as their owners.

By Holly Doan

Kinds of Winter: Four Solo Journeys by Dogteam in Canada’s Northwest Territories, by Dave Olesen; Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 268 pages; ISBN 9781-77112-1316; $14.99