In 1895 when the Queen knighted Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell, once a printer’s apprentice, newspapermen composed a ditty:

- When I was a boy I served my term

- As a junior imp in a printing firm

- I washed the windows and scrubbed the floor

- And daubed the ink on the office door

- I did the work so well, d’ye see

- That now I’m premier and a KCMG

Bowell quit school from Grade Four to scrub the floors at the Belleville Intelligencer and wound up owning the company. He was a drudge whose only escape was immersion in drudgery, clocking fifteen-hour days. Years later, when Bowell achieved fortune and fame, he kept a parrot trained to croak, “Wake-up.”

When Bowell died he received no state funeral. Even in life he was forgotten. Bowell spent a quarter-century languishing in the Senate to age 93. His papers in the national archives remained largely untouched.

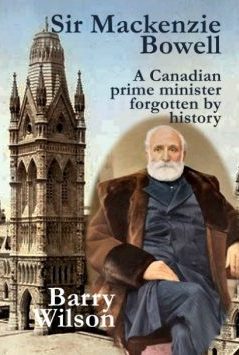

Sir Mackenzie Bowell: A Canadian Prime Minister Forgotten By History is an affectionate, candid portrait by Barry Wilson, for 35 years a reporter with the Western Producer. Bowell could have no more fitting biographer than an ex-newspaperman. “By any reasonable standard, his Canadian saga was an immigrant-makes-good success story,” writes Wilson.

Collective amnesia on Bowell’s tenure is forgiven. He was the Konstantin Chernenko of his era, a plodding apparatchik who faithfully toiled for the Party. A friend recalled Bowell was “decent and hardworking” but lacked “force,” “intelligence” and “modesty.”

Bowell did not become prime minister through caucus or grassroots support. His Conservative Party would not hold its first leadership convention until 1927. He served just sixteen months as leader before his ouster by cabinet rivals. He was “a competent workhorse,” writes Wilson.

Nor was Bowell entirely likable. He enjoyed backgammon so long as he won. “He flatters himself that he plays a pretty good game and thoroughly enjoys to win,” a reporter wrote in 1894. “If he is beaten, well he wants another game.”

On meeting the gracious Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani, composer of the haunting ballad Aloha Oe, Bowell considered her “ugly as a hedge fence.” Once aboard a Grand Trunk passenger train briefly held up by striking locomotive engineers, Wilson writes Bowell was so traumatized by the inconvenience even years afterward he would curse “uppity employees and their demanding unions.”

For all that Sir Mackenzie Bowell is a beautifully written and very Canadian account of an egalitarian society, then and now, without any landed gentry, where Mack the Printer’s Boy could make good. Wilson’s research is meticulous, though even he could not unearth elements of Bowell’s 1820s childhood to permit armchair psychoanalysis.

Bowell was a carpenter’s son who emigrated with his family from Suffolk at age 9. His mother died when he was 10, a family catastrophe that sent him to apprenticeship. Bowell was shop foreman by 17.

He rarely drank, never smoked, occasionally prayed at the office but was no proselytizing Methodist. He had a temper, once hurling a water glass at a Commons heckler, but a sense of humour, too. In an age of scoundrels in Ottawa, Bowell was never known to solicit a bribe or kickback. “A man must never weary,” Bowell said in an 1895 speech to the Young Conservative Club.

“If he puts his shoulder to the work, he must never hesitate but keep pushing, pushing until he attains the top,” said Bowell. “It is by plodding industry that you will be led to success.”

Mackenzie Bowell is Canadiana, warm and frank. If Canadians do not celebrate these stories, then who?

By Holly Doan

Sir Mackenzie Bowell: A Canadian Prime Minister Forgotten by History, by Barry Wilson; Loose Cannon Press; 276 pages; ISBN 9781-9886-57257; $22