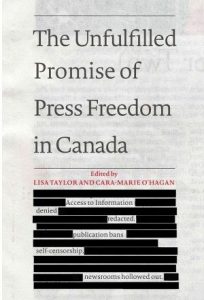

A new book from University of Toronto Press suggests press freedom in Canada is weakening as news media decline, and reporters genuflect to power in the face of growing job pressures. In The Unfulfilled Promise of Press Freedom, Prov. Ivor Shapiro of Ryerson University notes Canadian journalists could campaign to protect their rights, but don’t for a variety of self-serving reasons.

“The press could use its freedom more assertively,” writes Shapiro; “The argument for press freedom today is harder to make than before, because it rests on a greater burden of responsibility. The press could work harder to make this case.”

The point reflects our experience at Blacklock’s Reporter. The other day a Commons committee clerk threatened one of our reporters with an RCMP background check and lifetime banishment from Parliament Hill. The grievance involved alleged requirements in obtaining a public document at a public meeting by a member of the public, us. We told the clerk to put the complaint in writing and get ready to fight like hell.

The incident illustrates Shapiro’s lament. In Ottawa we see a steady push to control journalists and keep information from citizens on a day-to-day basis. Blacklock’s has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars and countless hours asserting our statutory rights. It’s pretty much a part-time job.

“To explain why news media sometimes hesitate to investigate and critique widely admired figures and institutions (including one another), it is sometimes suggested that Canada is a smaller world, a place where bridges can be so easily burned, leading to career obstacles and lost jobs,” writes Shapiro. “But surely journalists, who tend to be so dismissive of cowardice when it’s exhibited by senior civil servants or judges or politicians, should be shocked, rather than tolerant, when it is exhibited by peers.”

Media are the only for-profit corporations granted constitutional freedom from government regulation. Having won a reprieve from costly rules that vex other businesses, it’s not too much to expect that media managers spend a bit of those savings on something other than party hats and dividends for shareholders.

“The press could campaign for a freer press,” as Prof. Shapiro puts it. The fact many don’t is noteworthy but not profound. Canada has never had a golden age of press freedom, and our business like yours has its share of lightweights and poseurs.

The book’s observations are brought to life at the Parliamentary Press Gallery. Many shrink from confrontations with officialdom for fear of offending a future employer. Many others have no emotional investment in their trade whatsoever. Some just want to have fun.

The Gallery has $235,000 in the bank but could not be bothered spending a penny on submissions to Commons committees examining Access To Information and the state of dailies. When the RCMP in 2016 admitted to unwarranted surveillance of two Ottawa reporters, the Gallery did not utter a whimper. Minutes of board meetings indicate the Gallery was preoccupied at the time with hustling corporate sponsors for its annual banquet.

The Unfulfilled Promise of Press Freedom is candid and thoughtful. It belongs in every journalism school library. It casts a wide net in asking why media fight, and more interestingly, why some don’t. “No one is better positioned to educate the public about these issues than journalists themselves,” writes Prof. Bruce Gillespie of Wilfrid Laurier University. “If they fail to do so, they risk perpetuating the government’s framing of the issue as one of self-interested whining.”

Authors recount famous stories of CBC court challenges of government secrets and censorship, though the effect for readers is uneven. Accounts of Goliath versus Goliath are not telling. Doggedness is no virtue in a billion-dollar news corporation with a roomful of taxpayer-subsidized attorneys.

More compelling is the account of Robert Koopmans, former courthouse reporter with the now-defunct Kamloops Daily News. Koopman’s newspaper had a legal war chest of $300. “I was covering the first appearance in provincial court of a woman charged with murdering her husband,” he recalls, when a defence lawyer told Court that detectives were badgering his client for a confession. The Crown Prosecutor suddenly piped up and requested a convenient publication ban.

“For the first time, I stood in response and sought standing from the court to address the Crown’s application,” writes Koopmans. “I argued the Crown’s request for a ban was unwarranted in the circumstances and did not meet the legal test put forth by the Supreme Court of Canada. The judge agreed, and refused to impose a ban. As a result, I was able to report on the concerns of a lawyer about the treatment of his client at the hands of investigators.”

Press freedom is won and lost at the bail hearing, on the picket line, at the school board meeting, in confrontations with every petty clerk, meddlesome cop or bad-tempered judge. As Alan Borovoy of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association once put it, “If you want to change policies, you have got to be ready to have some trouble, to make a fuss, to point the finger, to name some names. You’ve got to be able to do that, or nothing changes.”

By Holly Doan

The Unfulfilled Promise of Press Freedom in Canada, edited by Lisa Taylor and Cara-Marie O’Hagan; University of Toronto Press; 296 pages; ISBN 9781-4875-20243; $29.95