Québec is cast as xenophobic, a caricature some Québecers have done little to dispel. Only the Québec Soccer Federation banned Sikh children from league matches; “They can play in their backyard,” the director-general said. Only a Québec lunch monitor humiliated a Filipino-Canadian boy who wanted to eat with a spoon. Yet in both instances, many Québecers were as outraged as anybody. The soccer league apologized; the school board was hit with $17,000 in damages from a provincial human rights tribunal.

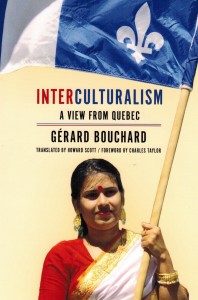

Sociologist Gérard Bouchard acts as an unofficial translator, attempting a reasoned explanation of why Québec does what it does. Interculturalism is thoughtful and eloquent. The inexplicable has a very simple explanation, Bouchard writes: “multiculturalism” tunes to a different frequency in Québec than it does anywhere else.

“There is in the francophone majority a very strong historical consciousness – we could say a memory under tension,” he writes. “It is a memory that is fueled by the feeling that the francophone majority still has an account to settle with its colonial past and with its present. Quebec, it should be recalled, experienced more than two centuries of domination.”

Interculturalism is no apologia for French-Canadian grievances. Francophones control most public and private institutions in Québec, Bouchard notes. They control media and government, and are the majority in 66 of 75 federal ridings. So, what’s the problem?

It’s obvious, he explains: nine in ten provinces are perfectly comfortable with multiculturalism in the knowledge that immigrants, especially their children, will inevitably assimilate into the happy majority that speak English, tolerate the Queen and enjoy Canada Day fireworks.

In Québec, this is precisely the problem. “Here, the long-term objective is to reach a point where all Québecers share responsibility for the future of the French language as the national language, with the understanding that for many of them French is a second or third language,” Bouchard writes; “All citizens of Québec, immigrants or not, are therefore invited to contribute to the cause of French in the continuation of past struggles.”

Interculturalism depicts a Québec society that is beginning to feel the walls are closing in. Québec today comprises barely 23 percent of the population; they are outnumbered by British Columbians and Albertans combined.

It’s a society that as late as 1986 saw the proportion of immigrants account for “around 7 to 8 percent” of its citizens – a ratio unchanged from the 1930s. Today it is some 11 percent, and projected to double by the 2030s. This means Québec will have the same foreign-born population that Saskatchewan had in 1910, but Saskatchewan did not nurse ancient francophone slights.

“Reflection on the management of ethno-cultural diversity in Québec has always had to contend with the same problem, the same tension: how do we think jointly about the future of the francophone culture inherited from four centuries of history, and the future of all Québec culture?”

So, Bouchard invites a consensus: if the rest of Canada can forgive Filipino schoolboys for eating lunch with a spoon, or understand why observant Sikhs wear turbans, perhaps we might permit Québecers to indulge their insecurities on old struggles.

The irony is noted.

By Holly Doan

Interculturalism: A View From Quebec, by Gérard Bouchard; translated by Howard Scott; University of Toronto Press; 224 pages; ISBN 9781-4426-47763; $19.57