Newfoundland & Labrador has per capita the greatest literary output of any province, producing a stream of wonderful novels and non-fiction accounts of island life. There were only 22 members in Premier Joey Smallwood’s 1949 Liberal caucus, but two of them – Herbert Pottle and Harold Horwood – wrote memoirs that rate among the most candid, insightful and intelligent depictions of Canadian political life.

With fame comes caricature. Newfoundlanders and Labradorians are long accustomed to being depicted as quaint, funny, hard-drinking bumpkins. In Most Of What Follows Is True, poet Michael Crummey of St. John’s laments the literary misrepresentation of his home province. Crummey has the self-awareness to note this has the ring of the Congolese bushman who protests National Geographic expropriated part of his soul when it took a picture, but the complaint stands nonetheless. His target is a certain U.S. novel that “caused me to foam at the mouth,” says Crummey.

First, the fame. “It’s hard now to remember what things were like for writers before Newfoundlanders began regularly appearing on major literary prize and best-of-the-year and bestseller lists,” writes Crummey. He credits the breakthrough to the 1993 Pulitzer Prize-winning The Shipping News by Annie Proulx.

“For the first time in Newfoundland’s history, local stories are being read and celebrated by ourselves and by strangers abroad,” he writes. “And being seen and acknowledged in this way makes Newfoundland and my life within it feel more substantial, more solid. That this place is in a book!”

Now, the caricature: “I was at a literary festival reception somewhere in the United States almost twenty years ago. I was talking to a festival-goer who had no idea who I was, which is generally my experience at literary events in the U.S. I mentioned I was from Newfoundland and was expecting the usual blank stare, but her face lit up. ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘I know all about Newfoundland.’ ‘You do?’ I said, and I’m sure my face registered my surprise. ‘Yes, absolutely,’ she insisted. ‘I just read The Bird Artist. Do you know it?’ ‘I do know it,’ I told her. ‘And I hate to break it to you, but you know nothing about Newfoundland.’”

The Bird Artist was published in 1994 by America novelist Howard Norman of Washington, D.C. It tells of a schoolboy painter, Fabian, in WWI-era Witless Bay. “I started the book years ago but wasn’t able to finish it,” writes Crummey: “From start to finish, it is complete and utter bullshit.”

Characters have Greek names like Odeon (unlikely); they encounter raccoons (there are none in Newfoundland); they eat scones for breakfast (!) and sea bass, lettuce and tomatoes for supper. “No such supper was eaten in Newfoundland at the turn of the 20th century,” says Crummey. There are no sea bass on the Grand Banks.

The novel is “Codco satire,” he laments: “It is impossible for me, and I think for anyone with even the vaguest sense of the realities of life in Newfoundland, not to feel insulted by the book’s cavalier use of the place for its own ends. I know from my parents’ stories what people endured simply to keep body and soul together in those communities. And it’s exasperating to see the world appropriated by someone with so little regard for the most basic truths of those lives.”

Such is the price of fame.

By Holly Doan

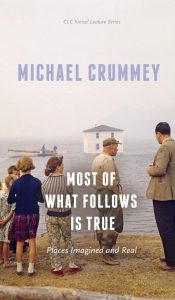

Most of What Follows is True, by Michael Crummey; University of Alberta Press; 72 pages; ISBN 9781-77212-4578; $11.99